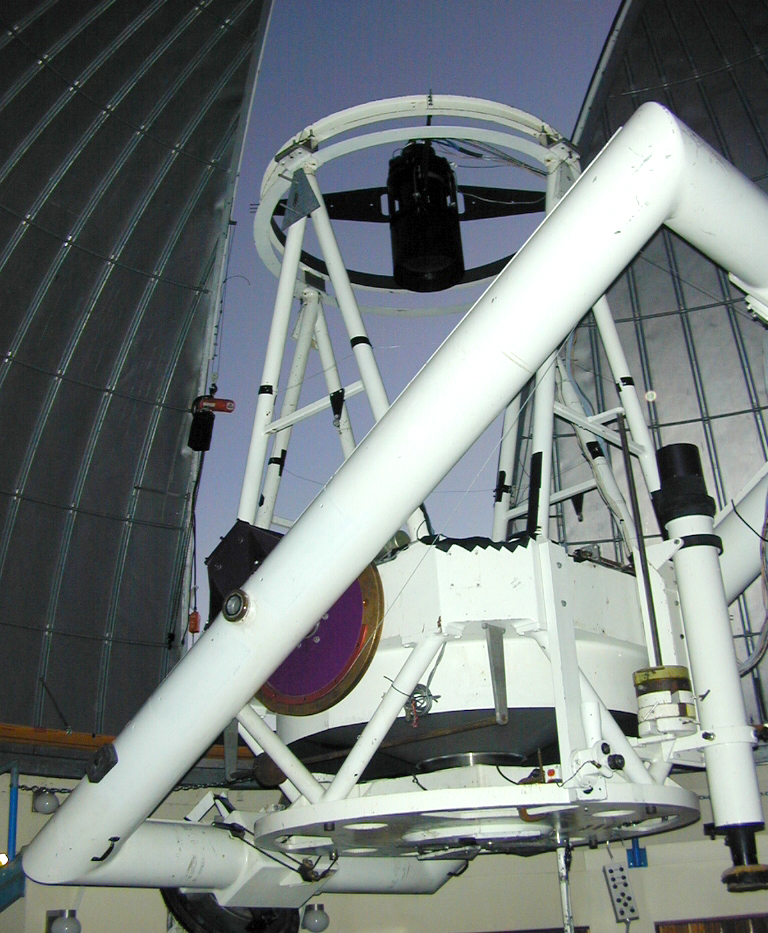

Nearly every evening the Steward Observatory’s 60-inch Cassegrain reflector takes thousands of photos, as it has for almost two decades. From this perch atop Mount Lemmon, at over 9,100 feet of elevation, just a few miles north of Tucson, astronomers use this amazing instrument to image small patches of the sky measuring just 5 degrees field of view, or about the width of your fist outstretched at arm’s length.

For 30 seconds at a time, the highly sensitive camera on the telescope gathers the faintest photons of light for a resulting snapshot of space with resolution of over 111 megapixels. These detailed stills are compared night-after-night to look for even the slightest changes, the key indicator that some unknown object in the far reaches of our solar system has been discovered.

On one cold night in January of this year, Carson Fuls, director of the Catalina Sky Survey, found one of these faint dots of light had moved, and then again the next night. From nearly 420 million miles away, he had discovered a new comet.

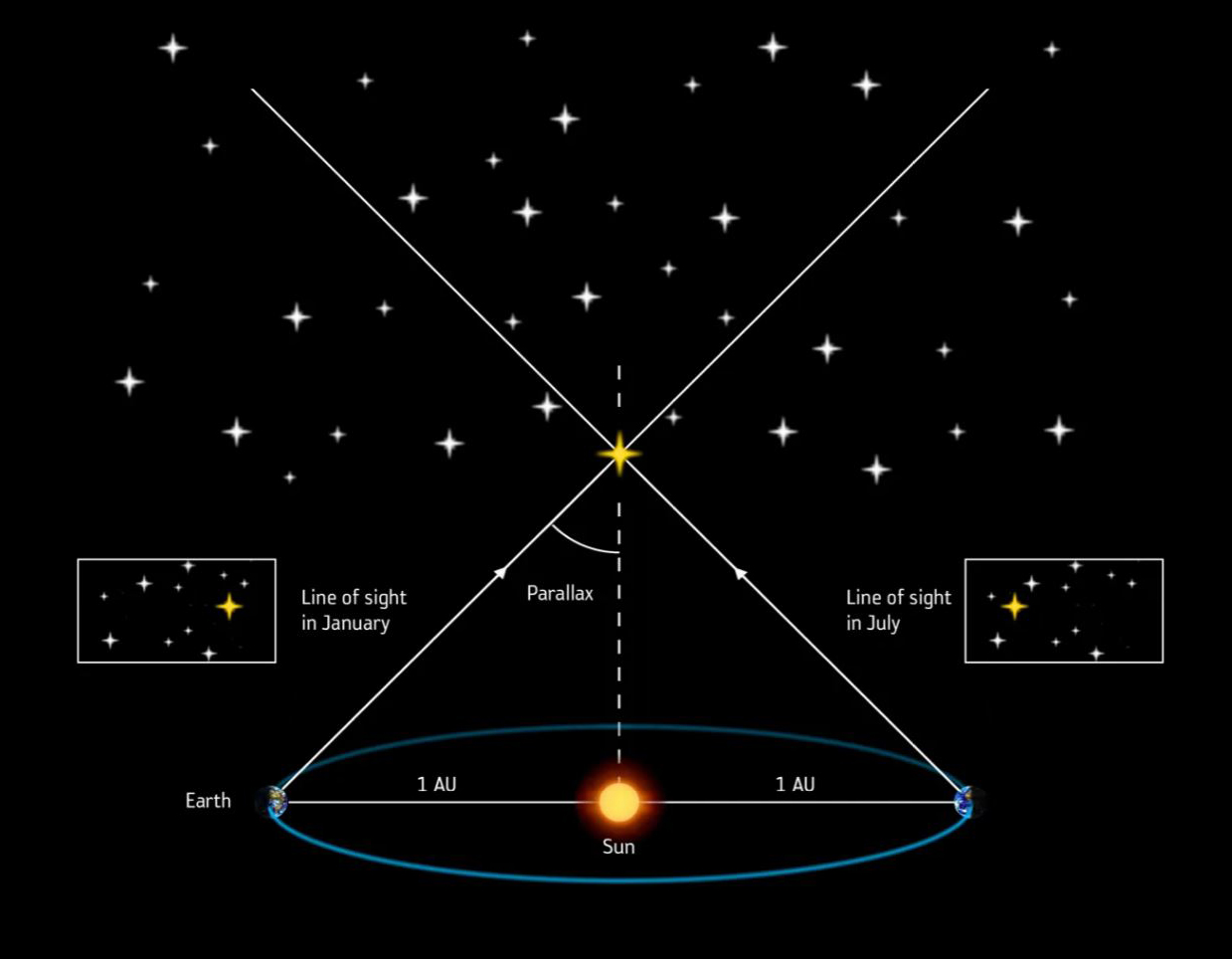

Once a new comet is discovered, telescopes around the world and in space begin to take followup observations of its path across the sky. Using a method called parallax, these additional observations track the object against the distant background stars to measure its size, orbit and distance. Like looking at a far-off mountaintop, a closer object, such as a tree or building, may appear to move quite a bit as the observer takes a few steps left or right. Similarly, as Earth orbits the sun and the object moves along its own orbit, the seemingly static background of space offers a standard that scientists can use trigonometry to measure against.

The Catalina Sky Survey has discovered thousands of comets, asteroids, and other near-Earth objects (NEOs) during its time. Commissioned by a congressional directive in 1998 to identify nearby objects a kilometer or larger in size, Mt. Lemmon was chosen for this mission and the University of Arizona has managed the discovery of more than 39,000 total objects, accounting for more than half of all NEO discoveries.

Comet C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) is the official designation for this newly discovered visitor, coming to us from the farthest reaches of the Kuiper Belt. Professional and amateur astronomers alike have contributed observational data, tracking it as having an aphelion of 244 AU, meaning its orbit takes it more than 240 Earth-sun distances away. One AU is 93 million miles, so that places its orbit as far as 22 billion miles distant. The last time it made a pass through the inner solar system was about 1,350 years ago.

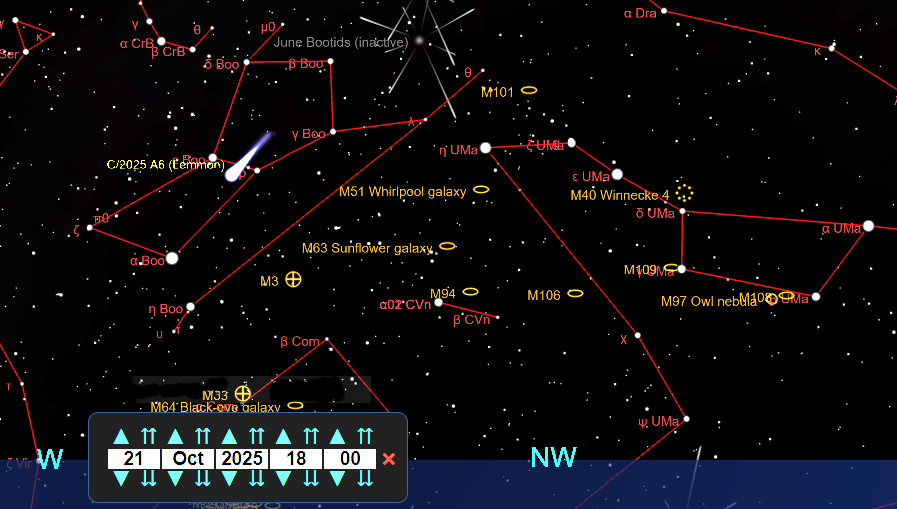

Through the month of October you can observe this long-period comet as it moves across Northern Hemisphere skies. Early October will find the comet in the constellation Leo Minor, the Smaller Lion, progressing to Ursa Major, the Great Bear. We know Ursa Major from its easily identifiable asterism, the Big Dipper. On October 21 the comet will make its closest approach to Earth, while in the constellation Boötes.

Look to the Western horizon just after sunset and find the bright star Arcturus. About 10 degrees above and to the right of Arcturus, or two fists at arm’s length, observers with dark skies may see the comet and its tail with the naked eye, but it will certainly be visible with a small pair of binoculars. As the sky gets darker over the following hours it will begin to brighten and move toward the horizon, till the tail disappears behind the mountains.

If you would like to learn more about the sky, telescopes, or socialize with other amateur astronomers, visit us at prescottastronomyclub.org or Facebook @PrescottAstronomyClub to find the next star party, Star Talk, or event.

Adam England is the owner of Manzanita Financial and moonlights as an amateur astronomer, writer, and interplanetary conquest consultant. Follow his rants and exploits on Twitter @AZSalesman or at Facebook.com/insuredbyadam.