DAN AND CHRISTINE Enright explain the origins of Little Portugal Bakery: “We honor our Portuguese heritage with baked goods and foods from the kitchens and villages of our Portuguese ancestors. Both our mothers came from the Azores in the 1960s.” At that time life in the Azores was primitive, with no electricity, no running water, and few cars. Both mothers emigrated to California’s central valley near Turlock.

The Azores are Portuguese territory, a volcanic island chain almost 900 miles west of Portugal in the Atlantic, where the North American, Eurasian and African tectonic plates collide. The central valley had well established Portuguese communities and a similar climate, so it felt like home. Dan said, “my grandfather’s back yard was entirely food, with not a speck of rock or grass — all garden, fruit trees and the most delicious grapes.”

Raised with these strong agrarian cultural and community roots, Dan and Christine looked for a way to continue the traditions while raising their family. They fell in love with Prescott, the climate and the rural feeling of north Williamson Valley. In 2021 they found property, built a house, moved in, planted an orchard of figs, apples and pears, and set up to raise pigs, turkeys and chickens. A couple of years later they started a Portuguese-heritage bakery business: the Little Portuguese Bakery was born. Christine had culinary-school training and they tapped into traditional recipes direct from the Azores and Turlock. “We are keeping it as close to everything that was done as possible,” says Christine.

Take the bolos levedos. Dan describes it as “what an English muffin wished it could be before it turned into a hockey puck. They’re soft and tender, with a touch of sweetness. The recipe comes from one island in the Azores where, a hundred years ago, they were baked on a hot lava chute.”

Other traditional bakery goods draw enthusiastic locals to the Prescott Farmers Market every Saturday. People of Portuguese descent and former visitors to Portugal drive hours to get the evocative, distinctive taste of biscocitos, tea biscuits in 14 different flavors, filhos, traditional light and airy donuts, massa sovada and papo secos, traditional Portuguese sweet bread and rolls, pao de lo, orange-scented sponge cake, and suspiros (“sighs”), little meringues that are light, crispy, melt-in-your-mouth and come in 27 flavors.

These and more are available every Saturday at the Prescott Farmers Market or online at littleportugalbakery.com. In everything Dan and Christine use their own farm eggs, organic flours, Farmers Market vegetables, local milk, butter and tallow (no seed oils), and prepare sauces and spreads from scratch.

Last year Dan and Christine bought and outfitted a food truck so they could expand their offerings to traditional breakfasts and lunch sandwiches, a perfect complement to the bakery line. Beef, pork and vegetables are sourced from Farmers Market vendors, and those vendors use Little Portugal breads for their own offerings. Dan and Christine tell me they are “devoted to the market and work with all the vendors as a community. We have not missed one Saturday.” The Little Portugal Bakery food-truck sandwiches feature authentic linguiça, smoked pork sausage marinated in garlic and wine. The recipe came “from Mom’s neighbor in Turlock.”

Check out the PFM Smash Burger (below), described as “house ground L-Bell Ranch beef and Quenga Farms pork patty, sauteed jalapeños and onions, cheddar cheese, topped with a confit garlic aioli on a rosemary garlic cheddar roll,” a less traditional but definitely delicious celebration of the Prescott Farmers Market.

What’s the future? Watch this winter for a line of traditional soups, both hot bowls and cold to-go containers from heritage recipes like kale, beans, potato and smoked bacon or bean stew with linguiça, accompanied by Portuguese cornbread (crusty outside, tender inside). Watch for filhos donuts freshly fried to order. Wow!

Dan has plans for the future. In seven to ten years Little Portugal Bakery could grow into a brick-and-mortar storefront, with bakery, traditional meats, sausages and cheeses, a restaurant and social hall — the second Portuguese hall in the state. Dan says, “We’re all about community, and we love being here.”

You’ll find Little Portugal Bakery every Saturday at the Prescott Farmers Market. The food truck is available for special events. Contact or place an order via littleportugalbakery.com or Facebook at littleportugalbakery.

IT'S WINTER, a good time to bake bread. If you’ve never made bread before, this is a basic training lesson, and if you’re experienced, consider this a refresher. Both are presented here with tips and lessons that you will never see in recipes.

First, this is a long-rise/short-work/no-knead method that starts three days before baking day. For almost all that time the dough chills in the refrigerator, developing elastic gluten and fermenting into delicious flavor.

Basic ingredients

4 cups water at room temperature, 3 tablespoons olive or other vegetable oil, 1½ tablespoons kosher salt, 1 teaspoon dry yeast, and about 7 cups of bread flour, either white or whole wheat

High-protein bread flour (12-16% protein) is essential. While the dough sits, wheat proteins bind together to build long elastic strands. The gluten bonds together to form a balloon-like surface that stretches over the carbon-dioxide and steam bubbles produced by fermenting yeast and evaporating water. That’s why yeasted breads are not dense as bricks. Elastic gluten also builds cohesion, so you can slice bread without it crumbling. You can add small amounts (1 cup) of other flours, like corn, rye, barley, or buckwheat for flavor. These are optional; none has enough gluten to work in bread alone.

Instructions

Start by pouring all the liquids into a deep bowl. Add the salt and yeast and half of the bread flour. Mix this into a slurry. Add other flours if you are using them, and then mix in enough more bread flour to make a soft dough, the consistency of drop cookie batter. Cover the bowl tightly and refrigerate. Your bread journey has begun.

Turn and fold the dough every twelve hours for two days. Here’s how:

Get your hands wet to keep them from getting sticky. Lift one edge of the dough mass. Stretch it up and over and then press it into the opposite side. Repeat this turn-and-fold process about four times, working your way around the bowl. Notice the dough changing as you repeat this process. At first the dough will be shaggy and tear. Then it becomes progressively more elastic and stretchy. You can see the gluten strands developing!

Timing: You could mix the dough on Thursday night, fold and stretch Friday and Saturday, and Sunday could be baking day.

On baking day you’ll have a bowl full of risen dough, stretchy, sticky and springy. Sprinkle the surface with flour and, using your hands, tuck that flour down around the sides of the dough. Sprinkle your work surface with flour. Sprinkle two baking sheets with flour. Pour the dough out onto the floured work surface. Scrape out the mixing bowl and set it in the sink to soak.

This recipe makes about 64 ounces of dough. For practice we’re going to divide this into 16 four-ounce pieces. I recommend using a kitchen scale (a very handy tool!), but you can just eyeball it. Cut the dough with a knife. Then dust each piece with a little flour and set them to the side of your work surface.

Take each piece of dough and form it into a tight balloon, using a bit more flour on the surface to keep it from getting sticky. Work toward forming a tight ball by folding the dough in on itself and pinching the bottom together, aiming for a smooth top and a pinched, puckered bottom. Lightly oil this little balloon and place it, puckered side down, on the baking sheet. Repeat with all your cut dough pieces. Cover with a damp towel or plastic wrap and allow them to rest for at least 30 minutes at room temperature.

Forming and cooking

For the Basic Bread Training experience we’re making flatbreads both on the stove and in the oven, English muffins on the stove, and rolls in the oven. Preheat your oven to 400 degrees. Heat a heavy skillet (preferably cast iron) over medium-low heat.

Start by making flatbreads. Working on a flour-dusted surface, take one dough ball and pat it into a thin round (about ¼ inch). Lightly dust with flour if needed to keep it from sticking. Transfer this flatbread to the skillet. After a few minutes the dough will show bubbles; flip it to cook the other side. You want gentle brown spots on both sides. Remove to a plate and cover with a towel. Repeat. At the same time you can make a few oven flatbreads. Use the same procedure for forming them. Put them on a baking sheet covered with a sheet of parchment paper, and bake them in the hot oven till they puff, about eight minutes.

Next make English muffins. Use half the remaining dough balls. Pat them down with your fingers to one inch and move them onto the medium-hot skillet. Several can sit side-by-side. After about eight minutes check the bottoms for browning, and turn them over. Look for nice browning on both sides. If you see burned spots, turn the heat down. They are done if when poked, the sides bounce back and do not hold the imprint. Remove them to cool in a pile.

Bake the rest of the doughballs as rolls. Leave them as is, round, tight balls, and transfer them, pinched side down, to a baking sheet lined with parchment paper. Brush them with oil and bake them till the bottoms are nicely browned and the tops slightly browned, about twelve minutes. Remove from oven and brush them with oil again to make a soft crust.

That’s it! You’ve experienced the mix, the feel and the bake for a variety of yeast breads. This is basic training for making loaves. Think of loaves as big rolls, so practice again, making larger and larger rolls.

I recommend you enjoy your freshly baked breads with amalou, a luscious Moroccan almond drizzle.

For 1½ cups of amalou you need a halfpound of raw almonds, 1 teaspoon salt, ½ cup olive, walnut or avocado oil, and ¼ cup of thin honey.

Toast the almonds in a microwave for 30 seconds at a time till they are lightly browned. Check after each timing to assure a light toast (mine take two minutes). Grind the almonds and salt in a food processor to a very smooth mass. Then slowly add the oil and honey, a tablespoon at a time. The mix should be runny. Add more oil if needed. Serve at room temperature with your delicious freshly baked bread — smackdown delicious!

Want more training? I’m teaching a Yavapai College Community Ed Crash Course on baking breads this spring. Call the Community Ed office at Yavapai College for information: 928-717-7755.

I love butternut squash, cucurbita

moschata. Let me count the ways ….

It’s sweet, nutty, smooth, and creamy.

It’s versatile, good in both sweet and savory dishes.

It can be baked, roasted, steamed, boiled, microwaved and fried.

It’s nutrient-dense, low in calories and fat, high in fiber, and an excellent source of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants.

It keeps for months at room temperature, for a week cut in the refrigerator, and for a year or longer cooked in the freezer.

It’s easy to grow, has a big seed, and comes up fast.

It’s an open-pollinated, non-GMO variety, grown for over 85 years.

The world loves butternut squash. It is the most popular squash in the world. In 2023 the global butternut-squash market was valued at $2.8 billion!

My garden loves butternut squash. We harvested 150 pounds this year. It’s easy to grow. Plant it in the spring after all threat of frost has passed. Consult with the Yavapai County Extension Office Master Gardeners for help (prescottmg@gmail.com, 928-445-6590).

In the meantime, butternut squash are in season now, with lots at the Prescott Farmers Market. Buy more than you need and store them in your kitchen. I have the best luck keeping them through February in a basket under my kitchen table.

And, what do I do with all those squashes? Simple: cut in half and bake, then serve with butter and salt. Or:

Butternut Squash Soup with Chili Oil

Here’s the recipe for 8 servings.

Collect the ingredients: You need a large butternut squash, 2 tablespoons vegetable oil, 2 teaspoons kosher salt (more to taste) and a big pinch of freshly ground black pepper. For the chili oil you need one dried New Mexico chili, broken into pieces (or a teaspoon ofAleppo pepper flakes), ½ cup of vegetable oil, and one whole big garlic clove, peeled.

In addition you need a large yellow onion, chopped, to make about 2 cups, a medium-sized sweet apple, chopped, 2 garlic cloves, chopped. Also measure out 2 teaspoons ground turmeric.

Mix together one cup sunflower butter, 2 tablespoons honey and 6 cups of warm water.

You’ll also want toasted pumpkinseeds for garnish.

Method

Cut the squash in half: Break off the stem. Stand the squash up. Using a chef ’s knife, start a vertical cut, from top to bottom. Get the knife started, then push down with both hands to cut all the way through. Open the squash. Scoop out the seeds with a spoon.

Preheat your oven to 400 degrees and put the squash halves cut-side-up on a parchment-lined baking sheet. Sprinkle them with one tablespoon oil, half the salt and half the pepper. Pop these into the hot oven and roast till tender (about an hour). Remove from oven to cool. Then remove skin and cut into pieces. Set aside.

While the squash is cooking make the chili garlic oil: heat a dry skillet over medium heat. Add chili pieces or Aleppo pepper and toast for a few seconds. Then add oil and garlic. Simmer gently for 10 minutes. Turn off heat and set aside for 30 minutes.

To finish the soup, heat the remaining tablespoon of oil in a large soup pot over medium heat. Add onions and apples and cook till golden brown, about 15 minutes, stirring regularly. Stir in garlic and turmeric. Add the sunflower butter/honey/water mixture. Then add the squash pieces and remaining salt and pepper. Simmer gently for 30 minutes, stirring occasionally. Remove from heat and, working in batches, blend soup till smooth. Return to pan. (I use a submersible blender, it works like a dream — no blender jar to clean out). Taste and adjust seasoning. Reheat gently or serve at room temperature.

To serve this beautiful golden soup, ladle it into a bowl, drizzle with chili oil and garnish with pumpkin seeds.

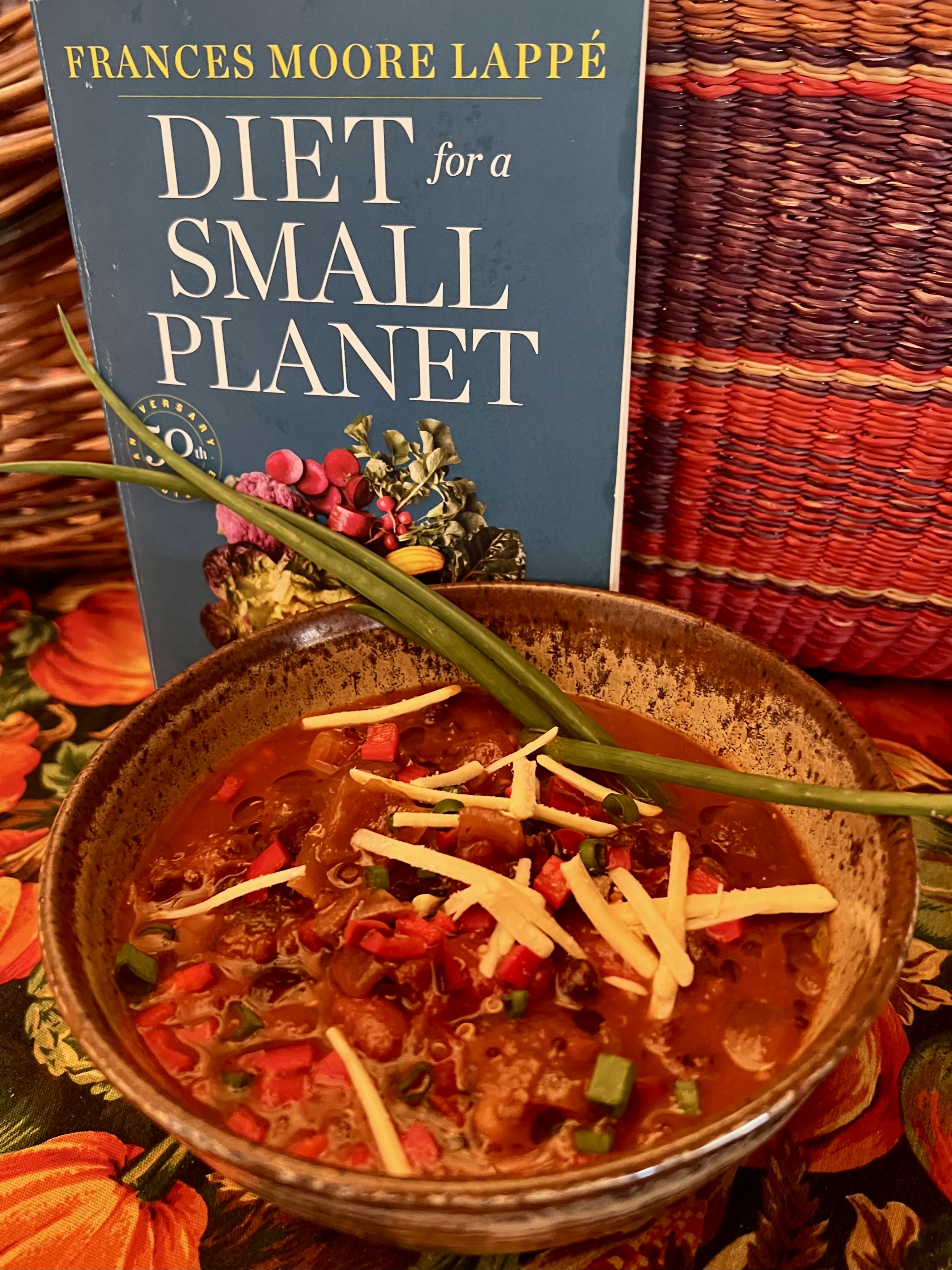

Chili (aka chili con carne) is a traditional Tex-Mex cowboy dish based on the ingredients they could carry — dried beef, dried beans and dried chilies. Annie Ryder and I reinvented it as a vegan/vegetarian dish when we taught Cooking with Natural Foods at Yavapai College in the late ‘70s.

We were inspired by Frances Moore Lappe’s book Diet for a Small Planet, an exceptional study that explains how a vegetable-centered diet could be protein-rich and address human-health, environmental and world-hunger problems. Diet for a Small Planet sold 2.5 million copies. It changed the way America eats and is “one of the most influential political tracts of our times,” says the Smithsonian National Museum. It’s been revised and reprinted five times, most recently in 2021. This 50th-anniversary edition is more pertinent than ever and well worth revisiting, containing over eighty new and delicious plant-based recipes from food stars like Alice Watters, José Andres, Mark Bittman, Sean Sherman and Mollie Katzen.

This chili recipe has weathered the test of time. I’ve taught it, cooked it, catered it and served it for almost fifty years, including the nine-year stint at Prescott College while I was food-service director. I made up huge pots and served hundreds, probably thousands, of bowls. I named it Crossroads Chili for the Prescott College Crossroads Cafe. It continues to be a big people-pleaser. I think I’ll serve it at the next Empty Bowls event in September. Meanwhile, you can enjoy it yourself. Just follow these steps.

Crossroads Chili

Step one: Gather what you need. For six generous servings you’ll need 4 cups of cooked beans. For the vegan version soak ½ cup whole-grain bulgur wheat in 1½ cups of warm water and set it aside. Bulgur takes on a meaty look and feel in this dish. (For the omnivore version you’ll need ½ pound of local or organic ground beef.) For both versions chop 2 large onions and mince 5 large cloves of garlic. Measure out ¼ cup olive oil and set aside. Measure and mix these spices: 1 teaspoon each of ground cumin and leaf oregano, 4 tablespoons of chili powder and/or sweet paprika (to taste). For the liquid component mix together 1 cup of tomato sauce, 1 cup of chopped fresh tomatoes and ¼ cup of good soy sauce (I prefer organic San-J brand). Set out salt, which you might want to add after tasting at the end. When you’re ready to serve you’ll need some crunchy fresh garnishes like chopped cilantro, green or red onions, radishes, bell peppers and maybe a grating of jack or cheddar cheese.

Step two: Build the foundation with caramelization and the Maillard reaction. Start with a thick and wide bottom pan that will hold 1 gallon. Heat at medium and add the oil, followed by the onions, garlic, spices and optional meat. Turn the heat to high and stir constantly. With the heat and oil the onions and garlic undergo a chemical transformation called caramelization that produces sweet, nutty flavors. When you brown the meat the amino acids (proteins) and fats are transformed by the Maillard reaction, producing deep, rich and complex flavors. Fat-soluble oils from the herbs and spices, including the chili powder, spill into the mixture. When everything is golden brown, move on to the next step. Don’t worry if some of the sugars stick to the bottom of the pan. This is the base foundation for full flavor.

Step three: Deglaze. Now reduce the heat and add the tomato and soy-sauce mixture. The foundation will bubble-spatter off the pan bottom and dissolve into the stock. Soy sauce plays an essential part in flavor, bringing rich umami depth to the mix.

Step four: Add substance, time and balance. Now add the beans and soaked bulgur (for the vegan version) and enough of their liquids to create a soupy consistency. Simmer over low heat for thirty minutes, stirring occasionally. Add more water if necessary. (Water evaporates faster at higher altitudes, like here, so keep an eye on it.) Taste and adjust for balance. Carefully add salt, chili or more of the other spice ingredients if needed. Taste and taste again. Get it perfect.

Step five: Finish fresh. Just before serving, garnish each bowl with a fresh, crisp garnish of chopped radishes, bell pepper, cilantro, red or green onions and/or grated jack or cheddar cheese. Your choice.

I hope you make more than you can eat in one meal, because Crossroads Chili gets better with age and will keep you warm and happy during the coming cold season.

Refrigerate for five days or freeze for months, and enjoy!

When someone says the word “summer” to you, what do you think of? Baseball? Picnics? Concerts on the courthouse plaza?

In my large Cherokee family in Oklahoma, it was gardening. Cherokee history is rooted in agriculture, particularly the cultivation of corn, beans, and squash (the “Three Sisters”) for thousands of years in the southern Appalachians. Cherokee women were the primary farmers, growing extensive cornfields and small gardens. This strong agrarian tradition was central to our culture, economy, and spiritual beliefs. The name for corn, selu, was also the name of the First Woman in our creation stories.

My mother thought nothing of putting 80 tomato plants in the family garden, along with beans, corn, peppers, carrots, squash, pumpkins and sunflowers. Ten percent was put in for the rabbits and other neighborhood critters, and the remainder was frozen, canned or dried for use till the following year. The kids picked wild berries, peaches and apples, and the entire family was involved in canning tomatoes, assembly-line style.

I can still be found in my backyard garden in the early morning hours, brushing off the dirt and having a breakfast.

So when I got a call from the Cooperative Extension office in Prescott asking if I would mentor a Yavapai woman as a Master Gardener, I accepted immediately! Did she have a history of gardening? No. Experience selecting plants? Nope. She was driven by the health disparities that exist between non-Native and Native people and a goal to revitalize the community garden on the Yavapai Reservation to grow healthier food, thereby positively impacting the health of the tribal community.

The statistics are shocking! US Census Tract data report that the average age of death for Native people vs AZ residents is 56 years vs 76 years. The leading cause of death of US indigenous people is heart disease and myocardial infarction. Next is kidney failure from diabetes. Diabetes in prevalent in Native communities and everyone who goes to the Phoenix Indian Medical Center is screened for diabetes.

My Yavapai friend and I have vowed to do everything we can to reverse this. These were our goals, with some input from tribal members.

• To provide a space for Yavapai Tribal members and their children for community events, gardening, and raising their own produce;

• To grow, harvest and prepare healthier food that is fresher and unprocessed, with less sugar and fat;

• To provide activities for children in a healthy environment where they are working as a team, getting exercise and being away from phones, television and computers;

• To encourage the planning, leadership and the satisfaction of completing a project for the good of families and the Tribe

It’s been three years since we started this project. So how are we doing? What was once a weed-filled and neglected space is alive with activity for a community project enthusiastically supported by the Tribe and kind businesses and individuals in this wonderful town.

Master Gardeners, through the UA Cooperative Extension, provided needed input in the planning use of the space and have regular work days at the garden in addition to donating plants. Lowe’s provided $2500 worth of tools, picnic tables, 50 bags of garden soil, several raised beds that now live at some homes of Yavapai elders, and a storage shed.

Improved fencing for the area has been paid for by the Yavapai-Prescott Indian Tribe (because there are deer and elk on the reservation who would look at this area like I was the Golden Buffet). Prescott College students provided labor in setting up garden beds. Prescott Slow Food donated three apple trees. Earl Duque and Ashley Fine donated plants and encouragement.

Trader Joe’s provided snacks and bottled water for workdays. Three REI Managers came for a day to spread mulch. Seeds were provided by Master Gardeners and the Cherokee Nation Seed bank.

The Indigenous Food Team is collecting recipes to use all the garlic, kale, tomatoes, squash, peppers and fruit coming from the garden.

And the best part? Members come to the garden and bring their children and grandchildren. They are seeing where their food comes from — a small seed, lots of care, and then delicious meals. This isn’t just a garden; it is part of the community.

The vision for the future of the garden includes classes on gardening and preserving food, a Fall Gathering, and collaboration with the Tribe’s diabetes-education program. Want to be part of the fun? Donations can be made though Prescott Slow Food, a 501c3 charitable organization, or for information contact me at imfromok@yahoo.com.

I started my research for this story at the only business in Skull Valley, The Forge Cafe, which is a restaurant, coffee bar and small store serving all natural beef, poultry and sausage from Iron Springs Ranch. The Forge was originally a blacksmith shop, then a gas station, then a coffee stop, and now a charming meeting site for Skull Valley folk and passersby. I am welcomed by a sturdy blonde, warmly smiling, Katie Ross. We sit down together over a delicious lunch. (I had the Outlaw Wrap: chicken, sweet chili bacon, avocado, red onion, red cabbage and secret sauce.) Katie is the Iron Springs Ranch manager. With a BS in animal science and years of experience, she and her firefighter husband John have managed this historic ranch (formerly part of the A Bar V) for two years.

Iron Springs Ranch is owned by Troy and Claire Eckhard, who are dedicated to turning this historic ranch into a property that focuses on restoring and building the health of the natural ecosystem. Troy and Claire also own The Forge, and today Claire is hands-on in The Forge kitchen.

Bringing the ranch health into ecological balance starts with building the soil by maintaining the plant cover and minimizing soil disturbance. We jump in the ranch ATV and Katie takes me to see how this works. We pass through a pasture, one side grazed by conventional methods, looking damaged, with dust and scraggly weed patches, and the other side grazed with a regenerative system, where the herd is moved frequently. That side is nicely grassed over. With regenerative grazing animals are restricted to designated plots and moved frequently to mirror wild-herd grazing. This rotation-grazing allows fields time to recover and restore.

Restoration time is dependent on the land, the weather and the climate. Today we’re in the middle of a drought, but I was thrilled to be exploring following a rare heavy rain. Katie says “We’re in the business of growing grass and healthy soil. The animals are secondary.” She’s not sure when the cattle will return to this plot. “When Mother Nature is your business partner, you have a lot of unknowns.”

Iron Springs Ranch cattle are handled with a minimum of stress, nice and easy. Katie knows them all. They come to her when called. They are born on the ranch and spend their entire lives there, all on natural bottom land and ranch hillsides. No cattle are shipped to CAFOs — feedlots where thousands are held in crowded pens, fed unnatural feeds and antibiotics that cause them to gain weight fast, so they can be processed after six months.

John manages the poultry operation, producing chickens and turkeys for Thanksgiving. He is also in charge of spicing the incredible chicken and beef sausage. This is pasture-raised poultry, raised outside with sunlight, grass and insects to eat and dirt to scratch around in. Poultry are housed in portable pens, called chicken tractors, that are moved daily. The chickens and turkeys can stretch and run and express their natural characteristics. The chickens are a heritage breed (Freedom Rangers) instead of the commercial types that are genetically selected to develop extra big breasts. They are grown for 12-18 weeks instead of the conventional six to eight weeks. Turkeys are produced for Thanksgiving only, so get your order in soon. (For ordering information see the Resources section online with this column at 5ensesmag.com.)

The ranch contains both bottom land and hillsides. Cattle are moved with a geofencing system. Each cow is fitted with a tracking collar. Kate shows me her phone. “All these dots are cows. The blue are steers. Red are heifers. I can click on each one to see who it is. The collars talk to our GPS signal towers.” Eight towers are installed around the 5,500 acre ranch to signal the collars to vibrate, keeping cattle from crossing grazing borders. Cattle can be herded this way to keep them rotating between plots (though they are still sometimes herded the conventional way, with horses). As we drive the ranch Katie explains that regenerative practices don’t take long to make a difference. This 100-year-old ranch shows a lot of improvement with just a few years of rotational grazing.

We end our tour at The Lookout, the site of one of the new GPS towers, with the beautiful ranch spread out below us. Katie again emphasizes that by working with natural systems instead of against them we can produce healthy soil, a healthy planet, healthy animals and healthy humans. Regenerative ranching protects soil and water quality, sequesters carbon and supports wildlife. Regenerative practices yield leaner, nutrient-dense meat with a healthier nutritional profile, increased vitamins and minerals, and lower antibiotic and chemical residues, and it tastes dang great! I brought some home. Delicious. It’s meat truly worth eating.

The word ‘squash’ comes from ‘askutasquash’ in the Narragansett language. The Narragansett people are an Algonquian Native American tribe in Rhode Island.

Squash originated in the Americas and was one of the very first domesticated plants, even before corn and beans. The squash family (cucurbita) includes all the summer-squash varieties (like zucchini), all the hardshell winter-squash varieties (pumpkin, butternut, acorn, delicata, cushaw, kabocha, kuri), spaghetti squash, and gourds. Wild forms of cucurbita are hard-shelled, extremely bitter and poisonous to humans. One of those ancestral cucurbits, the coyote gourd (cucurbita palmata) is abundant right here in Yavapai County. Evidence shows that mastodons and mammoths ate wild cucurbita before they died out 10,000 years ago. They were big enough to absorb the toxin cucurbitacin and lacked the taste buds for bitterness. Archaeologists have found fossilized seeds in fossilized mastodon and mammoth poop!

For thousands of years indigenous people have selected and cultivated less bitter, less poisonous and more tender squashes. Today we know one version of cucurbita as summer squash — zucchini, patty pan, yellow or scallop. They have tender white flesh and soft skin. They are abundant, fast and easy to grow, maturing in just fifty days. For best results summer squash should be harvested when small (or they grow into large, tough gourds). Gardeners of summer squash usually have overflows and are happy to give them away. If you don’t have squash growing, there’s someone out there who’ll be thrilled to hook you up. Otherwise the abundance of summer squash is available right now from all local farmers.

I was eager to turn my squash abundance into a frittata. This is an Italian pasta-and-egg dish that’s cooked firm in a cast-iron skillet and served at room temperature, in wedges. It’s a traditional picnic food. I started cooking on the 95-degree summer day and decided I could not stand the heat, the stove, the grill or the oven. So I took the ingredients and made a pasta salad.

Cook ½ pound spiral pasta (e.g., rotini) in boiling salted water al dente (tender but firm). Drain in a colander rinse with cold water, toss with a little olive oil and set aside. Chop one large yellow onion and mince 6 cloves of garlic. Heat a wide skillet over medium heat and add 3 tablespoons olive oil. Sauté the onion and garlic till they’re golden brown, stirring occasionally. While that’s happening, cut 1½ pounds of summer squash into roughly one-inch pieces. When the onions are ready, toss in the squash with ½ teaspoon black pepper, ½ teaspoon salt and a pinch of Aleppo pepper flakes or paprika. Continue to sauté, stirring occasionally till the squash is tender and lightly browned. Add 1 cup of coarsely chopped firm tomatoes. Mix well. Pour this mixture from the skillet into a wide bowl and chill in the refrigerator till cold, stirring every so often. You can move this step along by super-chilling in the freezer: set the open bowl in your freezer for 15-20 minutes and stir occasionally till cold, but not frozen. Then add pasta, ½ cup freshly grated Pecorino Romano or Parmesan cheese, and ¼ cup finely sliced fresh basil. Toss. Taste. Adjust with salt, pepper and olive oil. Serve chilled. Yum!

The next evening’s monsoon rain relieved the heat and I made the whole fritatta. The recipe is essentially the same except for the addition of eggs. It sets up to make a firm cake that can be cut into wedges and packed for lunch. Makes 6 generous servings using a 10½-inch cast-iron skillet.

Cook 6 ounces spiral or penne pasta in boiling salted water al dente. Drain in a colander, toss with a little olive oil and set aside. Chop one large yellow onion and mince 6 cloves of garlic. Heat the 10½-inch skillet over medium heat and add 3 tablespoons olive oil. Sauté the onion and garlic till they are golden brown, stirring occasionally. While that’s happening roughly cut 1½ pounds summer squash into one-inch pieces. When the onions are ready, toss in the squash with ½ teaspoon black pepper, ½ teaspoon salt, and a generous pinch of Aleppo pepper flakes or paprika. Continue to sauté, stirring occasionally till the squash are tender and lightly browned. Add 1 cup of coarsely chopped firm tomatoes and the pasta. Mix well. Remove from heat. Taste and adjust seasoning.

Preheat the oven or broiler to high. Spread the pasta-and-vegetable mixture out over the pan. Beat together 8 eggs. For a vegan substitute use Just Eggs. Set a medium-low flame under the pan and slowly add the egg mixture, distributing it evenly among the pasta and veggies. Let it cook undisturbed for a few minutes, till half-set. Now sprinkle with ½ cup freshly grated Pecorino Romano or Parmesan cheese and transfer the skillet into the oven or broiler. Cook till lightly browned and eggs are fully set. Let cool 20 minutes. Take 15 fresh basil leaves, stack them up tightly and slice thinly. Serve at room temperature garnished with basil shreds and cut into wedges.

Hot enough for ya?

It’s 100 degrees out right now and I’m in a midday torpor, thinking of chillin’ soups for refreshment and revival. Here are some hot tips for chillin’ soups:

1. Serve them super-cold, preferably half frozen with some ice crystals or poured over a few ice cubes.

2. Add enough water to create a thin consistency. Then adjust seasoning to taste. 3. Brighten flavor with a balance of sour and salt. What’s sour: vinegar, lemon or lime juice, and tangy dairy products (like sour cream, yogurt and buttermilk). Salt is, well, just salt, and for these recipes fancy salts work the same as plain table salt. But watch the quantity. Add a pinch at a time and taste, taste, taste.

4. Add some chilies. That may seem counterintuitive, but the heat from chilies comes from the chemical capsaicin, which tricks the body into thinking it is on fire and needs to cool down, producing sweat and stimulating endorphins and pleasure, triggering dopamine. A win-win-win situation!

I am in love with Aleppo pepper flakes. Aleppo pepper is moderately spicy with a rich, non-assertive flavor. It’s great as a garnish. You can find Aleppo pepper flakes in Prescott at One Root Tea and Herbothecary, 500 West Gurley. 928-778-5880

Makes 5 cups

½ cup dry pearl barley simmered in 3 cups of water till tender (about 40 minutes), then chilled

1 white or yellow onion, chopped

1 heaping tablespoon chopped fresh parsley

1 heaping tablespoon chopped fresh mint

2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

1 teaspoon salt, to taste

1 teaspoon pepper, to taste

Aleppo or hot pepper flakes to taste

¼-1/2 cup plain yogurt or buttermilk or thinned sour cream

Garnish: sweet paprika, finely chopped parsley and mint leaves

First cook the barley, using ½ cup dry, simmered in 3 cups of water till tender. This will take about 40 minutes. Then chill for a couple of hours. Meanwhile, finely chop one white or yellow onion, 1 heaping tablespoon of fresh parsley and 1 of mint. Heat 2 tablespoons of extra-virgin olive oil and add the onion, Sauté till the onion is slightly colored. Add the parsley, mint, and 1 teaspoon each of salt and pepper. Sauté for a few minutes, then add the barley and any cooking water. Stir together, then add yogurt. Mix together, taste and adjust seasoning. Add a pinch or two of hot pepper. I recommend Aleppo pepper, which is full-flavored but only medium-hot. Chill super well; put it in the freezer for an hour. Serve in small bowls garnished with a sprinkling of sweet paprika (or maybe more Aleppo pepper) and finely chopped parsley and mint.

Makes about 5 cups

½ of a medium watermelon, cut in half, seeded and coarsely cubed (1 pound of watermelon pieces)

1 large (about ½ pound) fully ripe tomato, cut into large pieces

½ red onion, peeled and coarsely chopped

½ cup toasted almonds

2 teaspoons kosher salt

½ teaspoon pepper

1 tablespoon sherry vinegar

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

1 green jalapeno or serrano (more or less to taste), stem removed

Garnish: ½ cup yogurt, buttermilk or thinned sour cream and finely chopped sweet or hot red pepper

Put all ingredients except the garnish in a blender or food processor and buzz till smooth. Taste and adjust seasoning. Chill exceedingly. Serve splashed with garnishes.

Makes about 6 cups

3 tablespoons vegetable oil

½-1 jalapeño pepper, minced (to taste)

1 2-inch piece fresh ginger, minced

3 cloves garlic, peeled and minced

Aleppo pepper flakes to taste

2 teaspoons ground turmeric

1 teaspoon ground coriander

1 teaspoons ground cumin

1 teaspoon curry powder or garam masala

½ teaspoon salt

4 cups plain yogurt (dairy or non-dairy)

1 large cucumber, grated

Water and or ice cubes to thin and chill

Garnish: Chopped fresh cilantro

Heat the oil in a small skillet over medium heat. Add the jalapeño pepper (if using), ginger, and garlic, and sauté till the garlic is soft and the oil is fragrant, about 5 minutes. Add spices and salt and stir for another minute. Transfer to a bowl and set aside to cool. Add yogurt, grated cucumber and water to thin. Taste and adjust seasoning. Serve topped with fresh cilantro.

Chef Tim Kispert smiles and welcomes me into the NoCo Community Kitchen, an incubator kitchen operated by the Prescott Farmers Market to promote and support small-scale entrepreneurs. It’s Friday morning and Chef Tim is prepping for the Saturday market.

Tim has a history of running restaurants in Palm Desert and in Prescott (Bill’s Pizza, Bill’s Grill, Red, White and Brew, and The Eatery at Yavapai College). Last year he worked the Chef in Action table at the market and, drawn by its vibrancy and personal interactions, fell in love with it. Then he stepped into his own business with Tim’s Korean BBQ.

As he preps for Saturday he explains his strategy: “I have a business model that is easy to handle, with minimal waste, and delicious. The menu is super-streamlined, featuring Kimchi Fried Rice with Beef Bulgogi (and locally sourced meat from L Bell Ranch) and Kimchi Grilled Cheese Sandwich,” with bread from the Farmers Market Little Portugal bakers.

Tim was born in Seoul, South Korea in 1970, and orphaned at six months. He considers himself lucky and blessed to have been adopted into a loving German-American family. He grew up on a five-acre hobby farm in Minnesota with two sisters. He knew nothing about Korean culture and rejected being different until his thirties.

At that point Tim was uncomfortable, unhappy and falling into addiction. Then he met Bill Tracy, the former owner of the Dinner Bell, Bill’s Pizza and Bill’s Grill. Through Alcoholics Anonymous he applied for a job at Bill’s Grill, and, Tim says “Bill changed my life.” That’s how Bill was. He hired Tim on the spot, helped get his teeth fixed, then gave him an open ended round-trip flight to Seoul with ten days off. Bill said, “Go get lost.” That was Bill, always reaching out with a deep belief in the basic goodness of everyone. He was a good friend of mine, too.

When Bill sold his Prescott restaurants and moved to Palm Springs to open Bill’s Pizza there, Tim followed. During this time Tim met Sarah (Yukyung Kim), also from Korea. He asked if she wanted to “eat through L.A.,” Tim says: “We ate high and we ate low, we ate everything.” He proposed with this offer, “If you want to spend the rest of our life with me, you’ll never go hungry.” She said, “That’s a pretty good deal.”

Bill Tracy died tragically in 2019 after falling from a restaurant roof. Now he lives in pizza heaven. Tim and Sarah returned to Prescott to work at Bill’s Grill and then at Red, White and Brew.

Now Tim and Sarah are Farmers Market micro-entrepreneurs, and Tim is loving it. He says “I just turned 55 and discovered that I have so much to learn. I’m getting a little older, and enough wisdom to be dangerous. That internal voice saying ‘more, more’ is quiet. Now I’m just enjoying the process.” Tim smiles; I eat Tim’s kimchi fried rice. We’re both happy.

Tim’s wisdom: “Life is a kitchen. Everything makes sense in a kitchen. You’re dealt a lot of disasters and come through them. I don’t get upset or take it seriously. Life is good. I love my wife, I love my life.” You can taste it in Tim’s Kimchi Fried Rice with Bulgogi Beef. Delicious. It’s my go-to-market lunch.

Organic jasmine rice, a long-grain, fragrant rice, is the base. It’s precooked and chilled before being stir-fried into this delicious dish.

Bulgogi is made from tender beef sirloin, sliced thinly, and then marinated in soy sauce, sesame oil, scallions, garlic, ginger and pureed Asian pears. (Tim offers an allergen-free version as welle.) Then it’s roasted and folded into the rice during the stir-fry, along with . . .

Kimchi, the Korean national dish. Kimchi is made from lacto-fermented vegetables, usually Napa cabbage, with plenty of garlic, ginger and chili powder. Kimchi is an excellent source of probiotics, vitamins and minerals. In Korea it’s eaten with every meal as a side dish or added to soup, stir-fry and, of course, folded into fried rice.

Kimchi Fried Rice is topped with a sunnyside-up egg for added umami, flavor and richness. Then all that is garnished with Tim’s own recipe, Gochujang Yum Yum Sauce, a sweet, savory and spicy fermented chili sauce. You won’t know how it tastes till you try it.

Any Saturday morning at the Prescott Farmers Market, look for Tim’s Korean BBQ tent, meet Tim and Sarah, and enjoy!

Hello Spring! In my garden that means the parsley is up as well as the cilantro and oregano.

Parsley is a biennial. It lasts two years, shrinks back in the winter, and returns the next spring, lush, green and ready to make seeds for the next round. Start it from seed once and it will re-seed itself.

Cilantro is an annual that comes up early and loves cool weather. As soon as the heat turns on it will “bolt” — stop making leaves, send up a stalk, and put all its energy into making seeds. Cilantro seeds are the spice coriander, making it a two-for-one package. Start cilantro from garden seed or organic coriander in late winter.

Oregano is a perennial, meaning it lives forever. My oregano bed is twenty years old! Oregano is very, very easy to grow. Start with a plant from the garden store or a rooted cutting from a friend or neighbor. It grows well in a pot. Oregano hibernates all winter. I cut the dry stalks back to the ground. By mid-April it’s back and flourishes all through summer and fall, when I cut and dry it for concentrated seasoning power.

These herbs are easy to grow in pots and carry a big nutritional bang. Parsley is a nutritional powerhouse, rich in antioxidants that strengthen bones, fight macular degeneration, reduce the risk of stroke, heart disease and cancer. A single tablespoon of parsley provides seventy percent of the recommended daily allowance of vitamin K, the important bone-strength nutrient.

If you don’t have these herbs in your garden, you can find them at the Prescott Farmers Market. Ask your farmer. Then try these light, bright, raw green sauces from Italy, Morocco and Argentina. They’re all parsley-based and similar, yet distinctive. I can’t make up my mind which one I like best, so I tested all three on my husband. They come together the same way, thrown into a food processor or blender and buzzed.

For Italian Salsa Verde use 1½ cups packed flat-leaf parsley, 3 peeled garlic cloves, 3 tablespoons capers, 5 anchovy fillets, 5 tablespoons fresh-squeezed lemon juice, and ½ cup each extra-virgin olive oil and water.

For Moroccan Chermoula use 1 cup packed cilantro leaves and ½ cup packed flat-leaf parsley. Add 4 peeled garlic cloves, 1/3 cup fresh-squeezed lemon juice, 1 tablespoon paprika, 2 teaspoons ground cumin, ½ cup extra virgin olive oil, salt and black pepper to taste.

For Argentinian Chimichurri use one large bunch of flat-leaf parsley, ¼ cup fresh oregano leaves, ½ cup of vegetable or olive oil, 4 peeled cloves garlic, 3 tablespoons red-wine vinegar, ½ teaspoon each of cumin and kosher salt, and ¼ teaspoon each of red-pepper flakes and black pepper.

All recipes make about two cups. For each, put everything into a food processor or blender and buzz till smooth. Taste and adjust seasoning with salt and pepper. Rinse out your equipment between mixes.

These sauces keep well in the refrigerator and are great in soups, on eggs, potatoes, pasta or vegetables. They are delicious as a marinade or sauce for meat, chicken or fish, as a dip, salad dressing or spread on sandwiches.

I made them all last night and taste-tested them on Mushroom-Pecan Fried Rice with Sliced Oranges and Tomatoes. For this simple dish you’ll need 2-3 cups of cold rice. Coarsely chop one pound of brown mushrooms and ½ cup pecans or walnuts. Heat a couple tablespoons of olive oil or butter in a wide skillet and slowly sauté the mushrooms and nuts, stirring constantly till the mushrooms are wilted and the nuts are toasted. Add the rice along with 1 teaspoon salt and ½ teaspoon pepper. Stir until mixed and the rice is heated through. Crack in one or two eggs and continue to stir over medium heat till the eggs set. Remove from heat, taste and adjust salt and pepper. Serve with sliced tomatoes, peeled, sliced oranges, and of course all three sauces to savor and compare.

Dear beginning gardeners and everyone else,

I love black-eyed peas because they are easy and fun to grow. The varieties of black-eyed peas include field peas, cowpeas, Big Red Zipper, Turkey Craw, Lady Cream Peas, Sea Island Red, Queen Ann, Pinkeye Purple Hull, etc. All are in the big Vigna unguiculata species and share common characteristics.

First, they are not really peas, they are beans, and have the same low-fat, high-protein, high-fiber, anti-oxidant and anti-cancer profile of other legumes. They are among the oldest domesticated crops, traced back over 5,000 years to western Africa. They spread to Asia, ancient Greece and Rome, around the known world and, with the slave trade, to the Americas. There are Asian Indian black-eyed pea curries, Chinese black-eyed bean cakes, African gumbos, Ethiopian coconut and black-eyed pea stews, Brazilian black-eyed pea fritters and Southern American Hoppin’ John (black-eyed peas and rice, traditionally cooked for good luck at the new year).

And here are the reasons why I love them:

You can plant the same beans that you buy at the grocery store (organic recommended) or find colorful variations from seed companies.

Planted after the last frost (mid-May to June 1) they germinate fast, in just 2-5 days.

They like alkaline soil, which is what we have here in the arid Southwest.

Like other legumes, they set nitrogen and improve the soil, so they make a good cover crop.

Regular black-eyed peas are bush beans and need no support (some specialty varieties are climbers and will need it).

They make a good forage crop for animals, including wildlife.

They are drought-tolerant, love dry heat and full sun.

They are fast-growing, about 70 days to full maturity, so you can plant them as late as July 1 and still get a crop.

They are resistant to bean beetles, a major bean pest.

They make great bean sprouts! Plant thickly, then thin your seedlings and snip off the root end — wonderful in a stir-fry.

They have edible leaves! Mutakura is a traditional Zimbabwean dish made with fresh cowpea leaves, onions, tomatoes and spices.

The pods make excellent green beans when picked young.

They are easy to pick because they hold their pods above the plants.

When picked more mature, but still green, they make delicious green shell beans.

Picked fully mature and dry, you can use them just like any other dry bean.

Dry black-eyed peas cook in just an hour, as opposed to three to four hours for common beans.

Like all dry beans they are easy to store. (Remember to freeze dried beans for two weeks after harvesting to kill bean-weevil eggs.)

Dry and sealed, they will keep for years.

They are used in many delicious and varied recipes around the world.

You can save the beans for seed!

From the last frost around mid-May through early August you can plant your own black-eyed pea plot. Make it as large or as small as you have space. For beginning gardeners you can plant blackeyes in a flower pot. Or plant them after harvesting early crops like garlic or onions as an edible cover crop.

So go get those cowpeas or black-eyed peas in any incarnation. Get ready to plant. Summer is coming!

Nutritional information from Food Struct, a great resource with charts and graphs and no ads!

Sources for unusual varieties:

Victory Seeds: victoryseeds.com

Southern Exposure Seed Company: southernexposure.com

Willhite Seed Company: willhiteseed.com

Urban Farmer: ufseeds.com

Greek Black-eyed Pea Salad

One more reason to love black-eyed peas. Makes 3 cups

3 cups cooked black-eyed peas or 1 ½ cups dry beans boiled in plenty of water for about 1 hour, until tender. Drained and cooled to room temperature.

Salt and freshly ground pepper to taste

1 tablespoon balsamic or red wine vinegar

2 teaspoons fresh lemon juice

1 tablespoon fresh chopped oregano or 1 teaspoon dried and crumbled

1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh mint leaves (optional, but very good)

2 tablespoons olive oil

1/2 cup chopped sweet onion (red or white)

2 large cloves garlic, crushed and finely minced

Zest of one orange (optional)

Crumbled feta cheese (cow, goat, or vegan)

Mix the cooked black-eyed peas, salt, pepper, vinegar, lemon juice, oregano, mint, olive oil, onion, garlic and orange zest. Taste and adjust salt and pepper. Marinate at least 4 hours. Top with cheese and serve at room temperature or chilled. Keeps up to one week refrigerated.

Leafy Goodness: Mutakura - A Zimbabwean Delight!

“Mutakura holds a special place in Zimbabwean cuisine, with a history that dates back generations. Passed down through the ages, this traditional dish represents the resourcefulness and resilience of the people. In the past, when food was scarce, the locals relied on the abundance of cowpea leaves to sustain themselves.”

https://inventedrecipes.com/recipe/440

Hoppin' John from Serious Eats

This version of the Southern New Year's Day staple features tender and earthy field peas cooked with fluffy rice and rich and smoky ham hocks.

Mania: An excessively intense enthusiasm, interest or desire — American Heritage Dictionary

It’s spring! The season has turned sunny, warm and green and I’m feeling itchy to get my hands in the dirt. I’ve caught seed mania, and maybe you have too. If so, we have help for you: Seed Mania! 2025. This fun, free, family community event is coming Sunday March 23, 1-6 pm at Prescott College.

This is the event's fifth year, started by Slow Food Prescott in 2019 and including a year break during the pandemic, with the goal of kick-starting spring. Join us to celebrate the season and learn what you can do about that intense enthusiasm to plant seeds.

We’ll have seeds, lots of seeds, to treat your maniacal condition. We’ll have seeds that grow well locally to give away. If you have seeds to share, bring them along (packaged and labeled with their common name, please) for the seed exchange.

We will have the famous Prescott Heritage Tomato seed available. I am honored to be the grower of these seeds for Native Seed/Search. I researched and discovered their story. Read “The Prescott Tomato Story” online at 5ensesmag.com.

We’ll have garden advice from local experts, businesses and organizations, for beginners, intermediate, and advanced maniacs to lant one flower pot or one acre. And we’ll have a list of backup support, garden coaches and mentors to contact for help through the growing season.

We’ll have activities for kids of all ages, games and giveaways, and hands-on immersive activities with compost, seed, herbs, worms and dirt. Walter Tortoise might even come out of hibernation for this!

I’m bringing special mud for seed balls. (Seed balls, also known as earth balls or nendo dango, consist of seeds rolled within a ball of clay and other matter to assist germination. They are then thrown into vacant lots and over fences as a form of guerilla gardening. Matter such as humus and compost are often placed around the seeds to provide microbial inoculants. — Wikipedia)

Starting at 1:30 and continuing every hour on the half hour till 4:30, we’ll have workshops to jump your mania into action, whether it’s the mysteries and makeup of seeds themselves, successful gardening soil and compost, microgreens, mushrooms or fruit trees.

Ongoing we’ll have music and food, beverages and snacks, and a tour of the spring-startup Prescott College garden, including chickens and ducks. It’s a real celebration! At 4:30 we’ll have an exceptionally delicious, healthy and free seed-themed meal cooked with locally grown, heritage foods — Tepary Bean Soup paired with Fresh Corn Sopa de Elote, Lighthouse Salsa, Roasted Squash Pumpkinseed Cornbread, Red Cabbage Coleslaw, Sesame Seedy Cookies and Mint Navajo (Greenthread) Tea (gluten-free and vegan options too).

Immediately following dinner service we’ll have a couple of speakers to orient our personal mania into thankfulness and community appreciation. Come at one, stay the whole afternoon, bring the family and friends — spread the word for the best seed-mania treatment!

"Pozole,” said my special friend Beatrice Diaz, “that’s what you cook for a big party.” She was born 92 years ago to an Ajo farm-worker family. While they were poor by today’s standards, on the ranch they knew how to celebrate life with good food from the land. Along with other festive foods, family, friends, neighbors and visitors always enjoyed pozole in big batches.

What makes pozole is nixtamal. There are many kinds of pozole, maybe as many as there are little grandmothers in Mexico, but it always contains the delicious, soft corn kernels called nixtamal. The name comes from the ancient Nahuatl Aztec language — nextli meaning ashes, and tamalli meaning corn dough.

Nixtamal is made by cooking and soaking dry field corn in an alkaline solution of food-grade slaked lime (cal). This processing technique dates back 3,500 years, and maybe started with ash blown into a pot on an open fire. Nixtamalization softens the corn, enhances its flavor, makes it easy to grind and easy to work. It makes corn much more nutritious and digestible, releasing niacin (vitamin B3), amino acids and calcium. Nixtamal corn (aka hominy) is ground to make masa for tortillas and tamales. If you visit a big Mexican market you will find dried, frozen and canned nixtamal. All the supermarkets carry canned nixtamal. Look for Juanita’s Mexican-Style Hominy.

This recipe is for red pozole, which is enriched with red chili sauce. If you use mild chilies, you can make it mild; use hot chilies to make it spicy hot. It makes 10-12 generous servings, enough for a party. The vegan variation substitutes mushrooms for the meat, and is pretty darn good.

Start with the stock by heating 3 tablespoons of vegetable oil in a large pot and adding 1½ pounds chopped mushrooms (for vegan variation), and the following chopped vegetables (for both meat and vegan): 1 onion, 2 stalks celery, 4 large cloves of garlic. Sauté until the onions are golden, then add 10 cups water and 1½ pounds of pork, chicken thighs or beef and some bones (or no meat for the vegan version). Toss in some spices: 2 allspice berries, 2 bay leaves, 2 teaspoons Mexican oregano, 1 tablespoon ground cumin and 1 teaspoon ground coriander. Bring to a boil, cover and simmer till the meat is tender and falls from the bone. For the vegan version, an hour of cooking is sufficient. Half an hour before the end of cooking, add 4 cups of fresh or frozen nixtamal/hominy (if you are using canned, add that later). Additionally for the vegan version add 4 cups cooked or canned pinto or black beans and 4 cups of cubed butternut squash.

While the meat and vegetables are simmering, make the chili sauce. Take 2 or 3 ounces of dried chili pods, mild or hot to your preference. Stem, seed and soak them in enough hot water to cover. They should soften up in about 15 minutes. Pour the chilies and liquid into a blender with 6 cloves garlic, 2 teaspoons salt and a teaspoon each of ground cumin and Mexican oregano. Buzz till very smooth; add more water if necessary.

Remove meat from the stock with a slotted spoon and cool for a few minutes. Remove bones and cut meat into bite-sized pieces. Return meat to cooking liquid. If you're using canned nixtamal, add 6 cups. Add the chili sauce and 2 chopped onions. Simmer gently for 30 minutes. Taste and adjust seasonings. Salt is usually required to balance flavors.

Traditional garnishes include finely sliced cabbage, red onion, radishes and limes cut into wedges. Serve it in wide bowls with lots of broth and warm corn tortillas on the side. Each diner adds their own garnishes, including a squeeze of fresh lime juice and a pinch of Mexican oregano as a personal blessing.

Pozole Rojo — Red Chile Pozole

Stock Ingredients

3 tablespoons oil

1 onion, coarsely chopped

2 stalks celery, coarsely chopped

4 garlic cloves, peeled and chopped

10 cups water, more as needed

1½ pounds chicken thighs or pork with bones or beef, or 1½ pounds mushrooms, cut into 1-inch pieces

2 allspice berries

2 bay leaves

1 tablespoon ground cumin

1 teaspoon ground coriander

Red Chile Ingredients

2-3 ounces dried New Mexico chili pods (mild or hot to your preference), stemmed and seeded

Hot soup stock or water

6 cloves garlic, peeled

2 teaspoons salt

1 teaspoon cumin

1 teaspoon Mexican oregano

Additional Ingredients

4 cups frozen or 6 cups canned nixtamal/hominy

4 cups cooked or canned beans (preferably black or pinto beans) for vegan version

4 cups cubed butternut squash for vegan version

2 onions, chopped

Condiments

Cabbage, finely cut

Red onion, finely chopped

Limes, cut into wedges

Cilantro, coarsely chopped

Mexican oregano

Warm corn tortillas

For the stock, heat the oil in a large pot and add the chopped mushrooms (for vegan variation). For both variations add the onion, celery and garlic. Sauté till the onions are golden, then add the water. If you’re making the omnivore variation, add the meat and bones. Add all the remaining spices..

Bring to a boil, cover and simmer till the meat is tender and falls from the bone, which might take a couple of hours. For the vegan version, 1 hour cooking is sufficient. Half an hour before the end of cooking, add 4 cups of fresh or frozen nixtamal/hominy* (if you are using canned, add that later). Additionally for the vegan version add the beans and butternut squash at this time.

Red Chile Sauce

While the meat and vegetables are simmering, make the red chile sauce. Stem and seed the chilies and soak them in enough hot water to cover. After about 15 minutes pour this soak into a blender with the garlic, salt and spices. Buzz till very smooth. Add more water if necessary.

Remove meat with slotted spoon and cool to room temperature for 15 minutes. Remove bones and cut into bite-sized pieces. Return meat to cooking liquid. Add the canned nixtamal/hominy now, with the red chili paste and 2 chopped onions. Simmer gently for 30 minutes. Taste and adjust seasonings. Add salt and more seasonings as necessary to brighten the flavor.

Traditional garnishes include finely sliced cabbage, red onion, radishes, cilantro and lime. Serve the pozole in wide bowls with lots of broth and warm corn tortillas on the side. Each diner adds their own garnishes, including a healthy squeeze of fresh lime juice and a pinch of Mexican oregano.

Notes on Ingredients

Dried red New Mexico chili pods are at most large grocery stores and all Mexican markets. I used Barker’s, which are packaged and shipped by Mesilla Valley Chili Company, Hatch NM. They come mild or hot. Remove stems and seeds. Wear gloves when handling the hot ones and don’t rub your eyes.

Mexican spices sold in cellophane packages in the Mexican-spice section of most supermarkets under the brand name of El Guapo:

Mexican oregano: More pungent and flavorful than Mediterranean oregano

Allspice berries: Also known as pimenton

Coriander and cumin: Toast and grind your own for maximum flavor.

Nixtamal/Hominy is corn that has been cooked and soaked in an alkaline bath. Available dried, wet, frozen, or canned (Juanita’s Mexican Style Hominy), it’s the precursor for tortillas, tamales and other tortilla-based foods.

If you’ve been to the Prescott Farmers Market on any Saturday in the past three years you probably noticed people carrying green camo buckets with “Prescott Community Compost” stenciled on them. If you were to ask one of these “bucketeers” for a peek, you’d see an assortment of familiar items: carrot tops, onion skins, moldy bread, eggshells, coffee grounds, citrus rinds and banana peels. These buckets full of kitchen scraps have become a visual representation of hundreds of community members turning would-be waste into a valuable resource with the Prescott Community Compost program. Food isn’t waste till it’s wasted!

Food scraps make up a significant portion of landfill waste. The City of Prescott does not have a green-waste composting facility, so most of the food waste generated in the city ends up in a landfill. Organic material in landfills takes up precious space and produces the greenhouse gas methane due to the anaerobic (no oxygen) conditions in landfills.

At our current rate of disposal, Prescott’s landfill will reach capacity within the next 45 years. Keeping food scraps out of the landfill benefits us by extending the life of the landfill, while also using those food scraps to grow more food. This is exactly what the Prescott Community Compost program does.

Each week at the Prescott Farmers Market, 300+ customers either exchange their green buckets for clean ones or dump their own containers of food scraps into a larger collection bin. On average more than 2,500 pounds of food scraps are then driven to the compost site at the southwest corner of the rodeo grounds.

The following day staff and volunteers work together with shovels and pitchforks to chop, water and mix those scraps with carbon-rich materials like leaves, wood chips and sawdust. The mix begins decomposing in large wooden bays, where it receives timed injections of oxygen through a solar-powered aeration system. After two months, staff and volunteers move the pile onto a concrete pad, one shovelful at a time, and continue to turn it for about eight months. During decomposition, microorganisms work so hard that the pile’s temperature heats up to 160 degrees. Once the pile cools and matures, the result is nutrient-dense compost that improves soil structure, fertility, and water retention. Local gardeners will tell you that this compost is just what most soil in our county needs.

Anyone can participate in the Prescott Community Compost program. The best part of this program is the people who work together to keep the compost piles turnin’ and burnin’. Three staff manage the compost site and lead the Sunday work sessions. Last year 74 volunteers donated more than 2,000 hours of their time to turn 54 tons of food scraps into compost. Here are ways to get involved:

• Bring clean, bagged leaves — no rocks, twigs, pet waste, yard waste or pine needles.

• Purchase an annual green-bucket subscription, which includes a clean bucket with sawdust each week — become a bucketeer!

• Contribute your food scraps at the Prescott Farmers Market — dropoffs from your own container are donation-based at the purple compost tent.

• Purchase bags of the finished compost for your garden or house plants.

• Volunteer at the compost site any Friday or Sunday, 9am-1pm.

• Make a charitable donation to support this nonprofit program.

• Spread the word!

Since the compost site doesn’t have the capacity to accept food scraps from every household in the area, the program also teaches individuals how to compost at home with neighbors. If you’re interested in starting a composting system but don’t know where to start, Prescott Community Compost offers a community bin-building workshop service. You purchase the materials and open your backyard to other interested community members to build a system together. PCC also offers a full-service compost system build, which includes all materials and labor to construct a three-bin system at your house. For additional information about these services, email compost@prescottfarmersmarket.org.

Our community is rich in resources if we’re willing to see them in a new light. The Prescott Farmers Market is proud to lead this community-focused program, and honored by your support since 2021. Whether you bring your food scraps to the market, purchase bags of compost for your houseplants or mention it in conversation to a friend, you can participate in and make a difference with Prescott Community Compost. For more information about the program, visit prescottfarmersmarket.org/community-compost.

by Kaolin Randall and Kathleen Yetman

Chef Molly Beverly is away; Kathleen Yetman is Executive Diector of Prescott Farmers Market.

Back in the ‘90s Chris and Elaine Vang moved to Chino Valley. They bought a small house on one weedy packed-earth acre. Chris says, “This is what we could afford.” I meet them on their front porch under an arching trellis of golden fall leaves, greeted by their slightly goofy black bull mastiff. Then we took a tour of the property.

Chris and Elaine use half their acre for a lush, rich garden and orchard, with fruit, vines, vegetables and animals. It includes several large shade trees, 15 fruit trees, including peaches, almonds, apples, pears, apricots and cherries, many trellises of elderberries, raspberries, blackberries and blueberries, and a full archway of grapes, 15 raised-bed and container gardens for vegetables and greens, thirty chickens in a comfortable chicken house, raised for eggs, three goats in a nice pen for milk and cheese (think ricotta, mozzarella, chevre and yogurt), and 16 Muscovy ducks, which have a pen but are allowed to roam because they eat bugs.

Also in the garden is a greenhouse, a couple of hoop houses and high tunnels made from stock panels (welded steel mesh), and some peaceful, cozy relaxation spaces with garden furniture. It’s a stunning garden oasis.

In this space Chris and Elaine grow most of their own food. Chris explains wryly, “We are ever so addicted to gardening. We smoked it the first time and got hooked.” Elaine adds, “We’ve always had a garden.” But the garden hasn’t always been the same. In the past few years they retired their original “in-ground” garden, with its nasty, invasive bindweed and elm roots, for a different design.

After 32 years of gardening in Chino Valley, Chris and Elaine changed their ways. Inspired by the Back to Eden documentary film (BackToEdenFilm.com), they restructured their growing areas with two principles in mind: sustainability — conserving an ecological balance by avoiding depletion of natural resources, and permaculture — an approach to life and growing food that copies the way things happen in nature to inspire ways for us to live without damaging the environment.

They changed their soil and watering treatment to include a deep mulch that starts with a layer of cardboard, then a layer of wood chips, and finally a layer of composted soil. This holds moisture, discourages weeds and brings up worms (which happen to love cardboard). It’s a no-till, self-mulching system.

They laid out the property incorporating several Food Forest layers: Layer 1 is shade trees (not necessarily edible); 2 is fruit trees and fruit-bearing bushes; 3, vines and shrubs; 4, annual and herbaceous plants, including vegetables; and 5, root plants, like potatoes.

They built raised beds filled with a bottom layer of logs for drainage, then mulch and composted soil. The beds improve soil fertility, water retention and soil warming. At the Vangs, this system of raised beds has gotten an enthusiastic response from both asparagus and sweet potatoes (recently they harvested forty pounds from a four-by-four-foot bed!).

These changes have made for an easier adjustment to the record heat and drought caused by climate change. Chris noted a ten-degree difference in temperature in the shade between the old in-ground garden and the new permaculture area.

I ask Elaine for beginner garden advice. She says “Start small. That’s how we developed this property.”

She adds, “The benefit of animals far outweighs the costs. Because of the animals we can be very efficient. Nothing is wasted. Leftover feed and bedding material and kitchen scraps go to the chickens. Chickens are excellent composters. The Muscovy ducks are expert bug-hunters, they do not disturb the plants, and produce lean, tender, red meat reminiscent of beef. And they are quiet. Manure from the animals builds the nitrogen base of compost that goes in the garden beds and on the trees. It’s a circular, self-sustaining, closed system.”

Elaine described it as her “happy place.” She gets so much fun and satisfaction out of the garden that she wants to share, so five years ago she set up the Let’s Grow Together! Facebook group focusing on local gardening. It now has loads of local gardening tips, stories, and advice. Two years ago she set up another Facebook group, Let’s Make Sourdough!, focused on local sourdough baking. (You'll find links to these pages in the Resources, below.)

All spring and summer Chris and Elaine grow and harvest their highly productive gardens. Elaine methodically stores the bounty for winter, canning, dehydrating or freezing. Lately she’s doing something different and better — freeze-drying. Elaine says the process is easier and results are more delicious, nutritious, storage-stable and convenient. She freeze-dries just about everything — fresh and cooked vegetables, soups, sauces, stews, meats, yogurt, cheeses, cheesecake, even guacamole! Elaine sparkles proudly before her shelf of bright, filled Mason jars.

You probably know that I’m also addicted to gardening in a big way. I’m impressed with Chris and Elaine’s approach, and I’m looking at my garden differently. I like the ease and quality of home freeze-dried foods. Thanks Chris and Elaine for the vision, the inspiration and the creativity.

Photos by Molly.

Back to Eden — How To Grow a Regenerative Garden

Watch for free at: backtoedenfilm.com

Let’s Grow Together! Facebook group

facebook.com/groups/673306179810015

Message Elaine for information on garden tours.

Let’s Make Sourdough! Facebook group

facebook.com/groups/343820468039067

Message Elaine for information on sourdough classes.

Freeze-Dryer: harvestright.com; dustinsfreezedryershop.com

(Please mention that you heard about it through Elaine Vang.)

I’m in love: I’ve got sweet corn and chilies growing in my garden. Wow! Pair these two up with cheese, butter or cream, and it’s rich, deep, fulfilling and passionate. Corn season runs from late July through late September. When the cobs are firm and full, I head for the garden with a basket. First I eat an ear or two right there, tossing the cobs aside. Then I feel through the firm husks for the plumpest, fullest kernels. Crack, crunch, I twist them off the plants and head over to the pepper plants. Sweets, hots, greens, red, rounds, skinnies, smooth, wrinkles, I stalk them. My fingers grope the dark foliage for the firmest fruits. With a quick snap, they are mine and I toss them into the basket.

Corn and chilies are great alone. You could just eat them chopped up together as a salad with a bit of salt. But marry them with the dreamy, nutty saltiness of cheese, butter or Mexican crema and you have a love affair.

(From the Mayan nahuatl, “toasted corn”)

You need: Corn, chiles, butter, olive oil, a lime, grated Romano cheese, salt. Shuck (peel off the green wrappers) six ears of corn, then slice the kernels off. That will give you about 5 cups of corn. Using a sharp knife with a wide, flat blade, cut the tip square, stand it up, and make smooth cuts down the cob, zipping off the kernels. Take one or two medium-hot large chiles and mince very finely. The heat resides in the seeds and membranes, so if you want a milder flavor, cut those out. If your chilies are picoso (hot), you might want to wear gloves. Chiles will burn through your skin, and affect anything you touch, so don’t wipe your eyes.

Melt a chunk of butter in a heavy skillet. Let it sizzle. Throw in the corn and chiles and ½ teaspoon of salt. Cover and cook over medium flame, tossing occasionally, until the corn is lightly browned. Sprinkle with lime juice and freshly grated cheese, or drizzle with the Mexican version of cream cheese, crema. Amazing!

You need: Corn, flour, large peppers or chiles, butter, milk.

First take two large sweet or hot peppers and roast them whole over an open flame on your gas stove or grill. Use a pair of tongs if you have them, and turn often. When they are browned and blistered all over, pull them from the fire and cover with a kitchen towel to cool for 15 minutes. Then cut the peppers in half. Pull off the stems and remove the seeds. Scrape off the skin with a table knife. Cut the flesh into little bits. Do not rub your eyes with chile fingers, and wash your hands really well. Now cut the kernels off six ears of corn (or use five cups of frozen corn). Throw these in a blender with a heaping tablespoon of flour. Buzz until smooth. Pour this into a saucepan and add a nice chunk of butter. Heat to a simmer, stirring constantly. Stir in the roasted chiles. Ecstasy!

You need: Butter, onion, garlic, corn, salt, large chilis, cheese, Mexican crema.

Cut the kernels off six ears of corn (about five cups). Fire-roast six medium to large chiles or peppers as described above, then cut them into wide strips. Coarsely grate ½ pound of really good nutty cheddar, Muenster, or jack cheese. Melt a nugget of butter in your heavy skillet and fry the onion and garlic, gently. Add the corn and cook till kernels are tender. Set aside to cool, and preheat your oven to 350 degrees. Butter a casserole pan and lay in half the peppers. Top with the corn and half the cheese. Cover with the rest of the peppers, a cup of Mexican crema and the rest of the cheese. Bake till heated and melted through, about 20 minutes. Orgasmic!

Maybe you don’t have a loving partner who plants you a passionate garden of chiles and corn. (If you cook up these recipes and share the results, you might find one.) Thankfully there are devoted growers around Prescott who sell them, but don’t delay. This is the season and in a brief month or two the gardens will be withered by the first frosts and the love affair will be over till next year.

Crema: Mexican sour cream, available in all markets, is mild and nutty.

Chiles and peppers: There are dozens of chile varieties, and all come from the same ancestral plant. They can be interchanged. Pick the heat level you like, and blend to taste.

Butter: I love Strauss Creamery organic butter from grass-fed dairy cows. Extra-virgin olive oil substitutes well.

Corn and chiles: Find them at Prescott Farmer’s Market on Saturday mornings.

My refrigerator is stuffed full of fall harvest bounty. The Farmers Market and the grocery stores are also loaded. Fall vegetables are at their peak of abundance and flavor. It’s minestrone season, time to make a big pot and store it away for winter. I make really big batches and freeze family-sized portions.

Recipes for minestrone (including this one) are open to many, many variations and substitutions. Even in Italy, minestrone’s mother country, each family, village and region has multiple versions that morph with the available ingredients and season.

This is not a recipe, it’s a technique. Get creative with what you have, but follow these steps:

Vegetables are loaded with sugars. When you expose them to heat the sugars undergo a chemical transformation called caramelization, producing browning and sweet nutty flavors. Similarly, when you brown meat the amino acids (proteins), fats and sugars react together and produce rich, complex flavors. That’s called the Maillard reaction. Herbs, spices and pepper flavors are oil- and heat-soluble. They dissolve and intensify in this step, forming the essential rich foundation of the soup.

Foundation ingredients for vigorous sauté till nicely browned:

> Generous dollops of olive oil, onions and garlic

> Ground or finely cut meats

> Sliced or diced vegetables like carrot, celery, zucchini, eggplant, mushrooms, potato, okra,

green beans, sweet peppers

> Fresh and/or dried herbs, salt and pepper

Over high heat add water and chopped tomatoes in liquid form. Bubble, bubble, sputter, you can hear the foundation dissolve off the pan bottom and into the liquid, forming a rich stock.

Now slow the process down to marry the flavors. Add delicate vegetables like spinach, chard, kale or cabbage. Cover the pot and simmer gently till the vegetables are tender.

Beans, grains and pasta are the substantial nutritional elements, the protein and carbohydrates that make minestrone a filling meal in a bowl. One or all can join the party, but each must be separately precooked.

Beans, if cooked from scratch (meaning dry), must be started hours beforehand. Or use canned beans. I cook big batches of beans and store them in the freezer for uses like this. Add them with some of or all their cooking juices after the vegetables are tender.