I CAN'T IMAGINE living without stories. I need well crafted stories to enliven and enrich daily life. I have time now to dip into works of imagination that are rich with humanity and landscape. I read novels of all sorts and watch television series that keep me from too much self-absorption.

As my activities slow down, accounts of the lives of others, well told, keep me willing to accept my lot and care about the world utside myself. As I read, good stories make the gray days luminescent.

I majored in English in college, thinking I could read stories for my class assignments. I was surprised to learn that good stories are an art form, scrutinized by erudite scholars. So my college years were not joyful wanderings through good stories; they were times of struggle as I pored over lengthy literary studies that revealed the secrets of good writing. I barely understood those articles. My mother would mutter that college was wasted on the young, and I understand that now.

Not one of my college courses introduced me to interesting, entertaining reading. Instead I was forced to study theories. Deliver me from theories. If you want to ruin a good story like Madame Bovary, then take it apart and analyze it. Develop a theory explaining why that novel is a masterpiece, but don’t ask me to explain your theory.

Why is Huckleberry Finn a great American novel? Read it and decide, but don’t ask professors to analyze it for you or the story is spoiled. Mark Twain found Huck and Jim in his imagination and told their story. They live in our memories, or they don’t. That’s my literary theory.

For years I was an English teacher in high-school classrooms. My students couldn’t understand what makes great stories, nor could I tell them without resorting to those academic terms and explanations that drown us in words and leave Huck floating away on his raft. Instead my hope was to introduce them to such good stories that they’d become readers for life, but they resisted when I chose stories that didn’t touch their hearts.

For example, my students would argue that there was no good reason to read Vanity Fair, a 19th-century British classic novel. After all, there are no people around now like the diabolic Becky Sharp — or so they thought. No selfishness? No greed or deviousness? I had mistakenly thought these bright teenagers would enjoy reading the story of a poor English girl who rises to fortune using her charms and manipulation. I loved it, but my students didn’t.

I remember that classroom argument and how hopeless it was to persuade privileged young people that Becky is real, that she lives today. I also remember the boys who took our copies of Vanity Fair to the bookroom when we’d finished our study of it. Carrying the load of books, the boys left our classroom and never got to the proper shelves. I can see them still, confessing to me and laughing because they’d dumped Vanity Fair in a trash barrel. (I have to add that I didn’t have the heart to punish them, knowing it had been a poor choice and they’d learn about conniving, selfish girls on their own.)

The stories that captivate us need to touch us with a reality we understand even if we live in a different era and culture. The story must have a humanity that is so well written it reaches us over the centuries. Good stories make an imaginative connection to the reality of our lives, but they require a knowledge in us that comes of living a while. I admit here that the choice of novel I made in that classroom was mistaken.

Television stories are wonderful sources of enjoyment for me now. In addition to my reading, I’m lucky enough to have access to television movies and series that bring to life people who live in a variety of settings, like Scandinavia, New York City or rural poverty anywhere. My children think me a curmudgeon because I’ve watched Masterpiece Theater for years. Not only do I delight in those renderings of classic literature, but I like well done contemporary televised stories too. I enjoyed The Sopranos, a masterful series that included humor, sorrow, cruelty and love.

I read this week of a man who recently built his 500th prison library at a women’s correctional facility in Connecticut. He’d been in prison himself, and read books in solitary confinement — books smuggled to him by other inmates with a pulley system of torn sheets. “Books gave me a pathway into the world,” he said.

I contend that the best books in his prison libraries are full of meaningful stories.

PART of my secret past includes not only high-school teaching, but ten years as a Christian minister as well. Five of those years were spent here in northern Arizona, where I served a small church in Dewey. Back then I was the only ordained woman in this area and a bit of a curiosity around here. Somehow I found that delightful, and enjoyed the attention.

During those years all sorts of people asked me odd questions as they tried to understand a woman clergy-person. One time a needy fellow came to the church door and asked me if he could see the minister. He was incensed when I told him I was a minister, and he refused the handout I offered, calling me names which I’ve conveniently forgotten. Still, I have many wonderful memories of those years, in and outside church life.

My role and robes encouraged people, especially children, to endow me with a direct connection to God. During a worship service, they would ask me to say aloud their concerns, hoping God could hear and help. One of my favorite memories is the time, back in California, when I was leading a worship service highlighted by a chorus of twelve children. They were to present songs from a musical called Jonah, and they sat together in the choir loft waiting to perform.

In the middle of the service I asked the congregation for special personal concerns that I’d add to our community prayer. After I heard from several members, they pointed to the children in the choir loft who were waving their hands for a turn. I hesitated because I assumed the children would ask for prayers that their performance would be a success. Instead, we heard the worries of those little actors: a teacher had to quit because of her illness; parents were divorcing; a pet dog suffered with a broken leg.

And so we prayed for the teacher, the dog, and for comfort during a divorce. Did those prayers matter? Even now, I’m asked that question by people who know of my clerical background. I wish I could say here that I know the answer, but I don’t. What stays with me, however, is a respect for those believers who pray.

In graduate school I took a course in prayer with a woman who was a believer. I so envied her and those students who also believed in the power of prayer. It was as if they wore cloaks that protected them from darkness. (Her name was Flora, of course.) The class covered prayer in many religions. Even though I learned a lot from Flora, I finished those studies without easy answers.

All cultures have a cohort of religious faithful who believe in protection and care from their gods, and they can turn from their everyday lives and find comfort and healing in prayers. They may reach toward that mystery in silence or in ritual. They might murmur, bow, or lift their hands as they seek help from a mystical being. Or they place their faith in a human leader or shaman to seek for them.

Believers have no problem with the mystery of prayer; it’s the curious, doubting mind that keeps the question alive. Is prayer a foolish gesture to make us seem righteous? Is it a selfish act to bring on special success? Does it really help the suffering? It seems we will always confront those questions. Unless the Messiah returns to earth, as some believe, humanity must wonder.

Nurses have told me that some religious patients who prayed for healing did better than those who did not. Was that God’s doing? Or was it the power of the psyche to lift the immune system to do its work? My professor never answered that question, but she did refer to incidents in which prayer seemed to change things, to make ‘the rough places plain.’

I’m not comfortable with the easy explanation that we alone create the healing needed for our souls and bodies; that feels arrogant. I think our peace and comfort comes from more than ourselves, and we are healed when we live in an atmosphere that is filled with a spirit of generosity and love. Whether or not the healing response comes from God, we seem to be restored by compassionate people in a community of support.

How can we pray in a setting that is hostile? I find in our country today a leadership that is ignorant, cruel and self-serving. The spirit created by such an atmosphere can’t be responsive to our needs and prayers. Yet I can’t turn away from the real world I actually live in, a nation I must confront before I can find a place to pray.

As I sat at her bedside, a young male nurse hurried into my niece’s hospital room to change her abdominal dressings. I was horrified that he was going to expose her naked body. After all, I was there to protect her modesty! However, the crisis passed when he looked at the patient, asked her permission, and she smiled at him as if to say ‘ignore my Auntie; she’s old and hasn’t a clue.’

Men in nursing! What a surprise. Who knew? Not me, evidently.

I see little news about the care we receive from nurses of all genders, so I choose to tell some stories about these wondrous caregivers. I want to remind us of the kindness, hard work, skills and understanding we find in nurses. They have mattered to me as I’ve taken tumbles and needed attention.

Not long ago I’d had an accident and had to be sedated because I’d fallen and broken some bones. My husband had to decide in a hurry about surgeries. He was at a loss and turned to a nurse, who explained the alternatives and told him what to expect. No one else was there to help, he said, and he trusted the experience of a nurse who seemed to know what to do. He hasn’t forgotten her name.

When a friend of mine waited anxiously in a hospital room after a diagnosis, a nurse suddenly appeared and sat beside her, like an angel. She stayed and told that nervous patient she wasn’t going to die. How wonderful, not to be ignored as we sit alone in fear!

I have a retired nurse friend who seems to know how to comfort me too. When I tell her my complaints, she affirms that I’m not crazy and my discomfort is real. If I must deal with some infirmity, she brings me flowers and large-print books to ease my tired eyes. She has that sense I’ve known in nurses as they witness pain and sadness, to be present and listen.

When I was a high-school teacher I befriended an aimless teen and told her she should pull up her socks and go to college, that she was bright enough to create a rewarding life. She chose nursing and grew to become a hospital administrator, nursing instructor and friend of patients.

I’m proud of that.

I know a nun whose calling was nursing. She held the hands of the suffering poor in Louisiana, worked with nursing students in a university, and became a hero to all her patients. She eventually gave up her religious vocation, and later retired from nursing, but she continues to befriend anyone who enjoys her humor and immense patience.

A friend who lived in England reports that home visits from nurses meant everything as she dealt with her four small children. In the TV show Call the Midwife, the nurses of 1950s Britain ride their bicycles to the homes of people who need care. The nurses roll up their sleeves and tackle any job that needs doing, from wiping the runny noses of toddlers to birthing babies.

I love the idea of ‘district nurses’ who provide help in rural areas where doctors and clinics are not available. They change dressings, give vaccinations, listen to grievances, comfort the dying, advise care-givers, distract worried children. I’ve learned that in some areas they arrive in mobile clinics with needed supplies.

Kristin Hanna's gripping novel The Women is about the women who served as nurses in Vietnam. We read of Frankie, a girl who enlists — over family objections — and is sent to a remote medical outpost: Frankie is overwhelmed by the chaos and destruction of war. Each day is a gamble of life and death, hope and betrayal; friendships run deep and can be shattered in an instant. In war, she meets — and becomes one of — the lucky, the brave, the broken, and the lost.

My favorite fictional nurse is Nurse Jackie, played by Edie Falco in that TV series. She is irreverent, outspoken, funny, rude and unfaithful. She breaks the rules, insults her superiors, and handles all crises with brilliant intelligence and compassion.

Nurses have been serving since the Revolutionary War, when they were organized by Abigail Adams. During our Civil War a cohort of women answered the cries of the wounded and assisted scarce medical doctors on the battlefields. While they had to confront bias against women serving as nurses to men, they prevailed, and their service evolved into the nursing profession in America.

I’m glad we have men in nursing. When someone answers the needs of those who are hurting, it’s time to set aside gender bias and welcome kindness.

.jpg)

My husband and I arrived at the courthouse in the late morning to witness a formal adoption event — a meeting with a judge to sign papers and transfer custody from the child’s caregiver to the family who’d chosen to adopt him. The atmosphere was friendly. Judge Brutinel was kindly. The two-year-old boy stood silent, holding the hands of his new parents and staring at the imposing wood-paneled courtroom. Within minutes he was legally moved from foster care to a permanent home in Prescott Valley.

The new parents, a gay couple in their thirties, looked eager and pleased. The two men seemed hardly able to keep from shouting, or singing, as the proceedings adjourned and we headed for the stairs that led away from ceremony into sunshine, tall trees, and a new life.

I had warned the eager parents that adoption wasn’t easy, that a two-year-old would come already imprinted with experiences of rejection, with times of confusing change, with attachments to other caregivers. He could be angry, ill or unable to control himself or learn. I’d cautioned against their decision, and the two men ignored my warnings.

That adoption went forward successfully, with parents who could manage any rejection and disobedience in a child they loved. They sometimes had doubts and anger, but I saw in them the strength and courage they needed to go the distance. Time has passed, and I see now an adult son who loves his parents. I’m still amazed.

My lack of confidence in the success of this adoption came from my own experience as an adoptive parent. My husband and I had adopted a baby boy, and I believed the child’s compliant nature was due to our wonderful parenting, but I had much to learn.

When our son turned two, we took him along to the adoption agency to meet his sister, an infant waiting for a new family. She was a cuddly baby with a lot of beautiful brown hair. We were thrilled with her—until the problems started. She couldn’t digest milk; she cried continually; and she didn’t seem to ever sleep. Because I was a teacher, given to searching for answers, I took her to doctors, read articles and consulted my friends. Nothing helped, except her father’s quiet singing as he paced the floor with her in his arms. I remember being brought to tears at the failures of my efforts.

Our baby girl grew into a terrible toddler who ate only waffles and refused to play nicely with others. Her temper never abated. She disliked games and toys and didn’t enjoy books. Her passion was our swimming pool. She could swim and play endlessly in the water. That’s where she laughed. That’s where she enjoyed friends. She seemed to belong there, to be a water-baby.

We investigated our baby’s heritage and learned that our daughter was partly Native American, and I believed her to be from a tribe near water. Maybe her love of animals came from her Native background too, because she could spend peaceful time with our spaniel and her puppies. Still, our investigations didn’t make living with her any easier. She hated school. She had a fierce temper. She bullied her brother. It was as if we were forcing this little girl to live in a place where she didn’t belong. She fought back, leaving us confused and discouraged.

I wish the adoption agency had been more helpful. They never told us of our children’s backgrounds. We were handed newborns as if the infants came as a blank page for us to imprint. I learned later that adopted children come with a genetic history that is far from blank. And my guess is that some of those youngsters have a deeper connection to their ancestral heritage than do others. Attention must be paid, I think, to the family history of adopted children.

Fortunately, adoption agencies do things differently now. Birth parents can remain in the child’s life, and the youngster has access to a background story, often in a scrapbook of pictures and notes. That seems to me a sensible solution to the trauma of a new placement. The small, silent boy in that Prescott courtroom received help to meet his birth mother and a brother as he was growing up. He acquired a sense of identity that I think made him feel complete.

My daughter left us early to be on her own. With my help she located her birth family, and now — with information and a new understanding — she has returned to my life. In fact, she’s become an amazing woman. Her insights are uncanny. I’m pleased that our connection is solid. As you might have guessed, she lives in a place with animals nearby and a river outside her door.

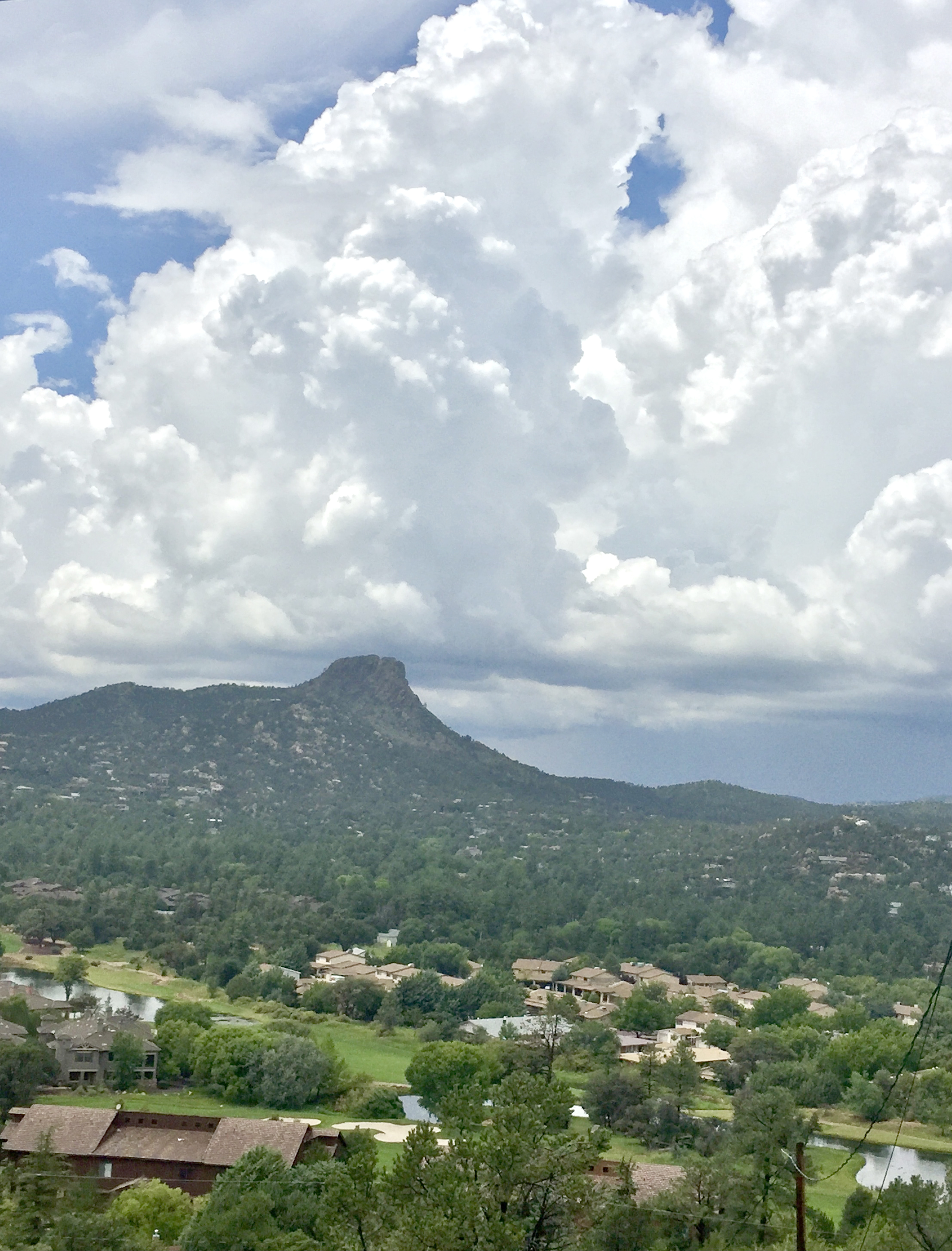

On a quiet day this summer, as I gazed out my window at the landscape and clouds, I realized that Prescott is now my home town. Even though I was born and raised in California — a long time ago — here I am, committed to Arizona, where I’ve lived for 36 years. My home is in Prescott. My friends are here, and I identify with this Arizona setting.

I need to write about this place that has come to be the center of my life for long enough that its streets, homes, weather and public places are my familiar world. How did I come to be in a small high-desert city?

I moved to Prescott because of a job offer, qand I stayed because I married a Prescott man. That’s the sum of it. My sense of belonging in Prescott has evolved, so I muse this morning how that happened, how I came to feel that the high desert is my home. I’m sure time has made the difference. The years have passed, and this place is now my settled world.

More than that, Prescott suits me. I feel I belong here despite my former years in huge, sprawling California. Maybe there’s something in our bones that knows where a person is meant to be. Prescott felt like a storybook place when I first moved here. I felt I’d come to Mayberry and would soon encounter Sheriff Andy Griffith. I enjoyed the western charm, especially our town square and row of frontier-style bars and shops.

In the beginning I thought Prescott was a place where people were safe and everyone was kindly. That was unreal, of course. (Sometimes magical thinking is fun.) The truth is more gritty: we have crime and poverty, our schools need attention, we have limited choices of supplies and services, and we have almost no affordable housing. What would happen if there were homes for all income levels?

I have reasons for staying in Prescott that are important to a sensibility like mine. Here I can find my way easily. There is one of everything — one library, one movie theater, one hospital, one city center. Prescott is neither huge nor sprawling, though overgrowth is threatening our open spaces. Development in the western areas could overwhelm what has been manageable. I hope our City Council will curtail growth and save us from dirty air, traffic and exploitation of the landscape.

Still, this is a place that makes sense to a simple soul like me. My car is serviced nearby, my doctor’s office is nearby, my supermarket is nearby. If you come from a big city, where you need sophisticated skills to manage the mess of streets and services, a small city is a welcome relief. Long lines for events are gone. Locations are easy to find, as are parking spaces. The city government is accessible. This place is livable.

I don’t miss California weather, either. I wish Prescott were balmy, but I tolerate the weather here because I’ve learned the tricks — when to venture out, how to manage air-conditioning, who to call when the snow is too deep. For an older lady like myself, the weather isn’t critical to my life. I’m indoors watching the quail, writing these articles, and enjoying a supply of good books.

What I must admit is that Prescott, like all sequestered places, is isolated from serious issues in America. Because we live in a remote high desert, we can pretend that the troubled world doesn’t include us, so we can stay apart from uncomfortable realities. I’m thinking of recent decisions that demand our attention, like ‘Alligator Alcatraz’ — built to imprison people without due process — and threats to free access to the truth of our past history found in libraries and museums. It’s as if our freedoms are being eroded.

While we’ve three colleges and a performing-arts center, we find it easy to hide from threats to American values. We can turn our backs on the end of health care for those who need it, the silencing of voices that disagree with powerful leaders, and the dismantling of crucial protections and regulations. Our local daily newspaper seems to avoid the crises outside our territory. Do rodeos really matter more than the struggles of the wider world?

I’m hopeful, though, when I witness some of our citizens protesting government overreach and cruelty. Activists remind us that the innocent are being punished in America, our land is being exploited, important institutions are being undermined, and laws are being subverted. The clamor of local protests shows that Prescott has the energy to speak truth to power, and I’m proud of my home town.

This is a love letter to public schools. They deserve praise, and I’m here to praise. I love schools more than ice cream. I’m serious about schools. My memories of public school are mostly good. I was not punished by nuns or expelled for anything, though I remember being made to sit under a teacher’s desk for a while because

I was a chatterbox. Miss Olson also had a closet where she confined other miscreants. That was in second grade. I never saw Miss Olson smile, but we didn’t think it odd. Our primary teachers were a crabby lot. Miss Hayes once accused me of cheating, and I was so hurt that I cried until she recanted.

My eighth-grade teacher was pretty, the only pretty teacher I had. She didn’t teach us much, but she loved tennis and taught us to play and score, an invaluable lesson. I wondered about her: why wasn’t she married? Why did she bother to teach us kids in a small elementary school? Was she hiding something? She belonged in high heels in a place with handsome men.

Little House on the Prairie was the highlight of my education in those eight years. I remember every volume of those novels, read to us aloud by our teacher in fifth grade. I learned no geography, no mathematics, no smooth cursive, but I could listen to those stories with complete concentration. (I couldn’t watch the TV series that came out years later because they weren’t perfect adaptations.)

My seventh-grade teacher, Mrs. Miller, was old, smart, and a model of perfection. She marked me forever the day she approached my desk and tilted the paper I was working on so I could write normally with my left hand. That moment changed everything! Years later, in graduate school, I thought of Mrs. Miller as I studied to be a teacher myself. I hoped to become like her — soft-spoken, wise, demanding and kind.

High school was awful. I attended a huge public high school that was ugly and tired of us. I do remember two good teachers who left their marks on my soul. Mr. Sardisco, a gruff Government teacher, took me aside one day and said, “Elaine, you should go to college.” What a gift! My Latin teacher, too, encouraged me. She was a homely taskmaster who took learning seriously. Otherwise, high school was a time of fretting over everything while enduring boring, ignorant teachers, or horrible gym trials, like field hockey. Still, I had a girlfriend who took me in hand and made life bearable, so I survived the fires of a school without a heart.

Those bad times haven’t changed my faith in public schools. Many schools are places where our children can learn to respect each other and maybe even come away educated. Like the real world, schools offer both the advantages of friendships and the pitfalls of awful demands, like field hockey. To overprotect our kids from the realities of a public education, I think, is keeping them from learning about the human condition.

I became a high-school teacher determined to change the lives of teenagers. I would be like Mrs. Miller and soar the heights of excellence. However, at my first teaching job my fellow faculty members, in an act of cruelty, voted me in charge of the school dance/charity food drive. I barely survived the confusion and preparations. My classroom that year was noisy, funny and undisciplined. I returned home exhausted at the end of the term, thinking about all I’d done wrong and ready to take up any profession that didn’t require teaching teens.

As chance would have it, there was a shortage of teachers in our area, and the principal of another school came calling. He persuaded me to try again at a new school that had large, airy classrooms and his guiding hand. It was either that or work for my father in retail. Fortunately I’d learned from my mistakes, so my teaching experience in the new setting went well, and I stayed until I retired to raise two children.

I wish our public schools everywhere were properly financed so there could be small classes led by teachers with skills and insights. I had to watch my son bused to a distant school during desegregation days, and it was an awful place. My daughter never adjusted to harsh discipline in her school. Maybe Miss Olson and her closet could have helped.

Failures like those don’t mean we give up. There are exceptional public schools everywhere, including in our area, and charter schools are a solution some have tried. But we must do better for our kids and offer free public schools that are not overcrowded or understaffed, but are welcoming places that deserve a love letter.

Aging has given me a place to look around and see my world. I call that vantage point my tower, a location from which I can observe. Now that I’ve stopped energetic activity and live quietly, I can view more of my setting. Our town, the country, and the diverse people who live here come under my scrutiny. The scene is enlightening, amazing, beautiful — and sometimes disturbing.

To be still and observe is a human activity akin to loving. I read of a Chinese student who studied in the US but missed his small village back home. He missed its dirt roads, its tiny shops, and the chance, he said, “to stand and stare.” In thinking about his remark, I realize that staring keeps the moment alive in memory. It’s a way to know, to absorb and even be changed.

I admire the dedicated watchers who take the time to stare. There are some among us here in 5enses, like AD Foster, who is fascinated with cats, and Ryan Crouse, an enthusiastic birdwatcher. Cats and birds matter, and they deserve observation by people who honor them with a close look.

Scientists are especially good observers. The famous scientist EO Wilson, featured in the TV documentary Of Ants and Men, lay in the dirt staring at ants for hours. Like Sherlock Holmes with his magnifying glass, Wilson watched ants. Out of a deep respect for the activities of these tiny creatures, Wilson learned of a universe beyond our careless lives. I imagine beekeepers would say the same.

My husband Don is a woodworker, and when he’s absorbed in his craft he focuses intently, like Dr. Wilson on his ants. It must be that all other things in the world fall away when these scientist/artists are at work. To be so taken with their vision that all else disappears is what sets these folks apart. We can’t know their findings till they create a finished piece or write an article about what is revealed in their stares into the hive.

Intensity of focus is not an attribute only of scientists or artists; it’s become an escape for everyone with a cellphone. I stare into my phone when I’ve an appointment and must wait in an uncomfortable chair; there could be a tsunami approaching and I’d miss it. My focus on Wordle or the news takes me away from the featureless room, the chair and the reality around me. I leave the present. Those who tell us to ‘live in the moment’ have a job to do in the face of captivating technology.

Because I’ve been a teacher, I worry that teenagers miss seeing the world outside their phones. They aren’t watching the world around them, never mind approaching dangers. I’ve no idea what matters have taken their attention. Is it seductions? Homework assignments? A friend’s personal life? A plan for adventure? Scandals at school? The stupidity of parents? I see in my list here many concerns to absorb a teen, but I’d rather they looked away from their phones and smelled the flowers.

Staring is an enriching pastime, but not so sweet if you’re a snoop. I saw a television program about a maiden lady who inherited her father’s telescope and used it to watch her neighbors, staring from her tower at their daily lives. She was a quiet, modest person who was, we learned in the mystery story, filled with hatred. There’s something about a person who trains binoculars on innocent people that’s creepy.

The practice of observing from our towers so we can find people we think are undesirable has lately been done by supremacists who want this country to be just for those whom they favor. When we seek out people of the wrong religion, the wrong skin color or ethnicity to eliminate them, the result is evil. I can recall when that vicious hunt was done by fascists in Europe, leading to the Holocaust, in which millions were murdered. Now, here in America, people outside the norm are losing their jobs, being deported or harassed on our streets, and I’m old enough to remember the horrors that resulted.

When we view our country from our towers, the sights ought to be varied, funny, impressive, and a jumble of differences. We are a crazy-quilt of humanity. We’ve managed to incorporate our differences into a community, and it took the energy of heroes who marched, debated, and led us forward into inclusion. Those heroes are still gathering in protest where they find attempts to stifle diversity and freedom.

Like that Chinese student who missed his little village, I miss admirable American leaders who were committed to helping our diverse population live healthy lives and flourish unafraid.

Today is a perfect day for reading. I’m quite sedentary and love to be surrounded by books. They are my delicious treats, my lovely pastime. At this moment I’m reading Lisa See’s The Island of Sea Women, a novel about Korean women who dive to the sea floor hunting the nourishment waiting there — abalone, octopus and crustaceans. They sell that food and feed their families with their bounty. These women are the ones who provide.

Women like them have been providing forever, but are rarely valued for their part in keeping humanity alive, so my thoughts today are about that injustice. Even in recent times we find women treated as little more than slaves. In some places, they are covered and not allowed to drive or be seen out of the home without a man; they are uneducated and devalued, viewed as necessary servants or commodities to be exchanged for goods. They have little protection from mistreatment, few rights of ownership, and endure scorn from people who think them inferior.

Not so long ago, if you were writing a tale for children or a story to teach morality to readers, your champion would be a man. If he showed kindness to a woman, he was exceptional, a paragon of goodness — Jesus is a good example. In recent history it took an uncommon generosity of spirit to see anything of value in a woman.

I’ve lived long years and watched as women I knew worked to gain respect and equity. A friend couldn’t leave a bad marriage because without a male partner she was denied credit. Many talented classmates of mine were excluded from some professions because they were women. Only teaching and nursing were open to us then. Female musicians were not given premium places in symphony orchestras till auditions were held behind screens. Colleges and universities had quotas for women students, and women were denied advancement because of fears that they’d get pregnant and leave the workforce forever. Reasons for such prejudice must have come from ancient beliefs that men are stronger, smarter and more capable — beliefs that originate in priestly teachings devised to protect men.

In accounts of women’s lives today, I find low opinions of women still prevail. Here we are, asking women to obey their spouses in marriage, paying them less in their jobs, giving inferior care to them in medical settings, keeping them in lower ranks regardless of their talents. JD Vance’s degrading remarks about childless women remind us that sexist bigotry is right in front of us now. In her recent study — after the last election — Sophie Gilbert calls this mentality an “onslaught of hatred” (“The Gender War is Here,” The Atlantic, Jan. 2025).

It’s clear to me that our screenwriters and cartoonists have infantilized women, portraying them as immature creatures who can’t think like adults. Not so long ago female characters in comic movies and cartoons were cute, silent or stupid, or — like Wilma Flintstone and Alice Kramden, their intelligence was usually hidden as they supported needy husbands.

Luckily it’s no longer a contest to see who’s smarter, who’s more attractive, who’s most able, because the evidence is clear: differences between the sexes are complicated. To assume that men are superior is foolish.

Now we’re advancing women in the military and sending them into combat. I find that an absurd triumph over centuries of bias. In the current film Six Triple Eight Black women in the military are given a mountain of work as an impossible challenge, and manage to finish the job and astound their leaders. What a satisfying story! This was the 1940s, when assumptions were that women couldn’t carry as much responsibility as men, couldn’t sustain difficult jobs or figure out solutions to problems.

In the novel I’m reading about the Korean women of Sea Island, Grandmother advises the divers, “Fall down eight times; stand up nine.” Good advice for women wherever they attempt difficult tasks even in this enlightened time.

I’m in awe of males who want to change their gender and become women. It seems that within our souls is an affinity for a certain way of being, so much so that some men find in the feminine spirit a comfortable place, and their bodies must conform. I’m baffled by it all, and yet I know of one who has happily made the change and lives a satisfying life. In the theater of my experience, I bow to the courage it took for a man to choose to become a woman.

Evidently there is more to the human being than biology. Instead, we are complicated, multifaceted, intriguing people who have inner lives that seek creative answers to the mystery of who we are.

“Reading is an act of civilization; it’s one of the greatest acts of civilization because it takes the free raw material of the mind and builds castles of possibilities.” — Ben Okri

In an effort to cut waste and abuse in government, our leaders in the administration are withholding funds to the Institute for Library and Museum Services. That’s enough national news to upset, frighten and anger me. I’ve never protested government spending on weapons — disturbing and horrifying news — but I’m protesting those decisions on libraries now. I see the cuts as a plan to limit free thought. Our leaders are strangling our liberty and must be stopped.

This harmful move to cut support to libraries is, I believe, the use of power to control us, and I’m furious. I can’t be proud of my country when our leaders are taking away the opportunity for everyone of all backgrounds and income to read books in an open, free setting. We have a thought police running rampant over our centers of learning, destroying the freedom to think for ourselves, to “build castles of possibilities.”

As lovers of libraries know, what we find in books is answers, perspective, thoughtful insights, stories of human interaction and exciting events. That’s where love is explained, where we hunt for truth, where a faraway place can be understood. The words in books engage us, spark our minds, bring us to insights about the human condition and its mysteries. Without books we are lost.

As you can tell, I can get worked up about reading, especially as an important activity for young people. One of my teenage students asked me, after one of my rants, “Is reading the most important thing?”

“No,” I said. “Love is more important.”

She sat back in her seat, relieved.

I provided daily newspapers for my students to read before classes started in the morning. For some, that was the only reading they did, even if it was just the crime stories. Local gang members were surprised to find their exploits written down in words. I like to think those news reports turned them into readers of books.

Libraries can also be places to rest. Once, when I arrived early at the downtown San Francisco Public Library, I found a crowd there at the door, a group of tired, homeless people waiting to enter a place where they would be safe and warm. I envision them reading too. If that library is denied enough funds to be open early, those people will suffer. Libraries matter.

My mother, an immigrant from Austria, went to work at 18, helping support a large family. She learned typing and shorthand from a book and became a secretary in an office overlooking the Los Angeles Public Library. That library gave her an education, and she became a lifelong reader who taught my sister and me to enjoy books. She told us stories at the dinner table from the books she read. Listening to her stories was like hearing a TV series on Masterpiece Theater. (I’ve no idea what my father must have been thinking as he ate his dinner.)

Here in Prescott I’ve spent a good deal of time in our public library, escaping chores, teaching a class of actors, encouraging memoir writers, even singing in a chorus at the Friday library concerts. While I enjoyed my time, I found myself among all sorts of other kinds of seekers — those interested in neardeath experiences, those who wrote poetry, or studied astronomy, or organized peace events. I even came upon a fellow working two jigsaw puzzles at a wide library table. To think of limiting the library staff or hours is scandalous. The cuts would deprive us of interesting creative opportunities and leave Prescott the poorer for it.

While I think of the library as a magical, beautiful place, like a castle in a story, I do have one uncomfortable memory of my time there. While wandering the stacks one morning, I tripped and fell, breaking several bones. My accident caused a fuss, a flood of EMTs, an ambulance ride, some nasty pain, and it scared my fellow patrons, who were there to find quiet. So I have to add here that even while strolling in a quiet library, disaster can happen and bring us back to an awareness of the fragility of life.

I’m told that President Trump doesn’t read books, and that’s enough for me to fear for the future of America. Without thoughtful, informed leadership by a person conversant with the teachings of history, we don’t have a President who understands his role, the planet, other cultures, or the value of compassion and humility. Leadership requires knowledge, and that knowledge comes from the patient work of scholars and artists whose words are found in books.

Trump’s administration is failing us.

Her photo is posted here next to my monitor. She looks at me with sad eyes as she stands in a kitchen, her hand on a counter. Her brown hair surrounds a pretty face with a hint of smile. Wearing dark blue scrubs with some sort of school emblem on the shirt, she seems prepared for her first job as a medical assistant — but she doesn’t look like she wants to work. She looks unable to move.

At nineteen, this girl, my granddaughter, appears to have lost the will to go forward. She’s a girl of silences, of the quiet stare. I wish she could tell me what’s causing her mood. She may not know the answer, leaving us unable to help. We assumed she was on her way to a life.

She didn’t show up to take that job. She disappeared into the city of Albuquerque, and I must ponder the loss of a girl who passed all her courses, ticked the boxes, obeyed the rules — until she left. I don’t know why, but I can see in her face that she’s miserable.

If she took drugs to feel happy, then that’s a story with a desperate ending. If she wandered till she found a friend, that too can be worrisome. If she stowed away and sailed to the tropics or joined an army, we’d have been informed. If she went on a crime spree, we’d have learned the news. There seems no proof that she’s made it alive.

This absence is like a wound. It is sore, constant, distressing. I can’t believe in a positive outcome, that she’s all right, smiling, that she’s found a place to be. I’ve only to glance at the photo to know this wound is open, and I’m helpless in the face of that reality.

Meanwhile my days go forward. The chipmunks raid the feeder outside the kitchen window, the sun shines on bits of snow, and the national news continues to upset me, frighten me, anger me. As with my personal worries about a missing child, I feel helpless to set things right, to revise the government’s crude stupidity and hasty decisions. It seems they’re not keeping watch over climate, or minding the needs of the people. My helplessness is like a burden I must carry, made more desperate by my missing grandchild.

This week my friend sent me photos of herself and her pals at the annual Women’s March on the town square protesting harmful, self-serving decisions by our President and administration, decisions that target the poor, insult our allies, and dismantle the protections and services of our institutions. (I liked their banner: “Ikea has a Better Cabinet.”) I’m touched by that effort to show strength and humor in the face of power. Their protest is a way to stand up and speak out, displaying a critique instead of helplessness.

We’re in a time of national crisis. It’s not okay to leave Europe to cope beyond its means. It’s not okay to eliminate institutions we need, like national parks, public schools, a fair tax system or safeguards in our health system. I confess to a helplessness as I learn of this ruthless outrage, and I feel like a weak witness to a growing takeover by a tyrant with enough money and followers to change a democracy into what works for the few. I can write a letter, I can vote, I can stay aware of growing malevolence and support protest. Still, I feel I’m witnessing a dreadful smashing of precious traditions while I stand helpless.

In the past I’ve known this kind of helplessness while leaders rode unrestrained over free societies. That rampant bullying evolved into a world war, into murderous killing. Back then we didn’t believe fascists could prevail, that whole countries would be overrun. It seemed impossible, and our helpless refusal to get involved earlier resulted in the suffering of millions.

I wish I knew how to respond in the face of our government’s trajectory away from sanity and compassion. My feeling of helplessness destroys energy and paralyzes the will to act. I do know a real danger exists and the wrong people have too much power, because I have good information, led by intelligent journalists, wise friends and academics whose values I share. They write, they blog, they inform. They inspire me to write my emails and letters.

I wish I could write a letter to save my granddaughter and bring a look of hope into her eyes. I have no address. I wish she’d ask for help. I wish there was an article I could read that would show me a way to comfort her. Instead, she is gone from our touch, and we wait.

It comes without permission, random and fierce, eating everything in its path. It’s a destroyer as potent as war and more senseless than gangs of vicious marauders. It will take your home, kill your pets, undo your plans and make you vulnerable to a frightening unknown. It’s the fire that burns everything you love.

In Southern California a horrendous fire has destroyed whole portions of communities I knew as a child. Here in Prescott, where I write my articles, I can imagine what is now gone, and I hold in memory what I remember as a pleasant neighborhood, a grove of orange trees, and the open lots and streets where I played. In that Southern California town I taught in the high school, attended a church, and helped in my father’s shop. The only fires I knew of back then burned in a European war, where I felt far from that holocaust.

News of the Second World War, with its murderous treatment of Jews, the destruction of European towns, the suffering of populations who were bombed and starved, came to us only in short edited radio broadcasts in the evening. For us children the war was a story with bad guys. So we played ‘war’ in our vacant lots and used sticks as toy guns to shoot fictional Germans and Japanese. We subscribed to no newspaper, and the foreign battles were unreal to me until gold stars appeared on windows in our neighborhood, and I learned that people grieved the loss of their sons.

Scarcity was serious during the war — shoes, tires, butter — and rationing limited our supplies and activities, but our area wasn’t bleak. The doctor came to our house when my sister fell down the basement stairs. A milkman arrived at the back door with glass bottles topped with cream. We walked unmonitored to school. We played dodgeball in the street, and rarely had to stop for a car. Our one radio, in the living room, featured Saturday-morning programs for kids. I now realize how very long ago that was: before television! before the internet! before Walmart!

Looking back now, it should be evident that I think of those days as blissful. I was proud of my little school and reliable parents. My mother was a neighborhood activist. She went to the Mexican area of town and started programs for the kids, including scouting. She began a parent/teacher group in our school and created a book club for moms. She taught my sister and me about classical art and music, encouraged by our father, who played mandolin and saxophone. None of the mothers I knew worked outside the home, but my mother would have been first in line for a job if it had been allowed.

That picture of Southern California in the past is an embellished memory, of course. I must confess here that I’ve left out some hard truths. I realize now that my little world was a sort of ghetto, exclusive and separate from our Mexican population. Everyone looked the same where I lived: white, tidy, and secure. The mothers stayed home and cared for everything. I assumed they liked that role, one of obedience without choices. I thought all America looked like our community. I never heard another language spoken, even Spanish. I no longer call that ghetto ideal.

Los Angeles was a thriving city where my father worked. No one imagined that police harassed Black people there or that the poor areas were neglected. No one imagined that fire and civil disorder would erupt. Yet here we are. People have rioted in benighted places in the city, and now fire flattens the suburbs. Some of Los Angeles looks war-torn. I remember the city as wondrous, eminent and wealthy. I remember apartment buildings and a Sears store. We didn’t venture there except on special occasions, and we took the trip in a red streetcar! I remember that my mother liked to window-shop — look in the store windows on the busy streets. I don’t remember ever going inside and buying anything.

Now, a mindless fire has leveled much of that California world I still dream about — its innocence, and ignorance, the clear air and reliable orderly ways. It’s now a place of destruction, where folks mourn for their lost, burned world. Fire has turned order into chaos, revised everything. The tokens of the past have gone. I wonder if the victims will ever turn to nostalgic memories like I do. My heart breaks for them as they wander their empty, scorched properties and search for any part of their lives that might have survived — a cap, a soft toy, or even a saxophone.

One of the burdens of growing older is losing things. You name it, I’ve lost it. And I’m not pleasant about it. I’m annoyed. My passport is gone. I had it on my desk, and now it’s gone. I’d like to blame the gods, or my husband, but that doesn’t work.

I don’t want advice about my anxiety over lost things. I don’t want you to tell me it’s not important, or it will turn up. I don’t want your wisdom. I want my passport. When something is missing, I feel incomplete, off-center.

If everything is in its place, the world is going to keep turning on its axis and I will sleep well, content that life is orderly and I belong here. Till I find what is lost I lose that certainty, the safe ground. I feel like I’ll never find happiness, never enjoy a good day, or be pleasant to live with.

I’m one who knows where everything is because I make sure everything is in its place. Ask me where you can find a pair of scissors; how about a wool scarf? A cookie sheet? When I know where everything is, there is a completeness to things. I’m not a philosopher who agonizes over a faulty theory, I’m a grandmother who needs things to be where they belong.

For the wise seeker, a lamp illuminating the darkness is a help to manage a troubling search. A lamp brings hope; it represents a way forward. The clarity it brings softens our anxiety and brightens our outlook. We need not be afraid in the dark if we have a lamp to lead us. If we light a lamp of calm, of composure, of humor, we find lost things. Some people think of the Bible as their lamp. Some are devoted to a loved one who banishes darkness. My lamp is a friend who finds things. She isn’t here today, so my passport is still gone.

I’m told that suffering a serious loss moves us toward compassion. If we know what it is to lose a partner, a pet, a knee, a home, or love, we earn a wisdom that makes us more understanding of the pain of others. Though we suffer, mourning is a process that develops our souls from innocent to maturity. It’s as if we go through the painful wilderness before we can find the meadow, the opening, and we emerge more able to sense the hidden needs of people around us. A nice thought. I’m not sure I believe it.

Annie Dillard, my favorite philosopher, wrte of the rent we pay by being alive, and that rent is the losses we suffer. I like that metaphor. She writes:

. . . her smile has widened with a touch of fear and her glance has taken on depth. Now she is aware of some of the losses you incur by being here — the extraordinary rent you have to pay as long as you stay.

It seems cruel to have to learn to cope with the loss of strength, the loss of people and so many of the props that make life bearable. We shed those parts of our lives and lose them with grief. Yet, Dillard says, we are more wise for having gone through mourning and loss. I’m reminded of a woman I knew who mourned the loss of her cat deeply, but she was not so difficult to console as another who refused to admit that the loss of her pet bothered her. That person got cranky and angry at life. It seems we must pay that “extraordinary rent” of mourning to grow compassionate.

Our memories of loss will send us into sorrows, but a sharp memory can lift us out of self-pity too. If you’re a poet, like Dylan Thomas, you can transform your sad memory into words like this:

And as I was green and carefree, famous among the barns

About the happy yard and singing as the farm was home,

In the sun that is young once only,

Time let me play and be

Golden in the mercy of his means

And green and golden I was . . ..

My passport has not emerged from its hiding place, and I have to admit that I don’t travel anymore, don’t need a passport, and must give in to a new reality, that I’m aging out of the passport community and live now in a quieter, more settled, place, where I read about the South Seas of Robert Louis Stevenson and the American South of Toni Morrison. Those visits have their beauty. They are quieter and less encumbered by the necessity of remembering to take a passport.

I’ve lived long enough to be a bit cranky about Romance, the forever love we see on the Hallmark channel. I’ve known marriages I thought were perfect end in collapse. I’ve seen besotted teens marry and promise faithfulness — till the birth of a baby. My own story is troublesome, too. It seems we must endure some shitty stuff, some poor choices, before we’re done. It’s a gift to learn from it all.

Love is Not Enough is the title of a book on child care I’ve not forgotten. It startled me as a young mother, since the stories I knew of motherhood and Romance seemed to say that love is all you need. Instead, I learned that more is demanded of a parent — like guidance, discipline and boundaries. I also learned that more is demanded of a relationship than a powerful attraction. It took the slings and arrows of real life to teach me that lesson.

Why are we seduced by the myth of Romance? I’ll blame television, romantic stories and wishful thinking. They gently persuade our vulnerable souls that we can find the perfect partner and enjoy lives of affection and plenty. Those of us who’ve known sorrow in love and seen dreams dashed no longer have stars in our eyes. Anyone who’s observed lovers and dreamers knows what might be around the corner.

An appealing part of Romance is that it’s an answer to despair and loneliness. It turns cloudy days sunny and makes us feel happy, confident, ready to take on what comes. It’s the best antidote to life’s stresses, like a delightful elixir that sets the world right. The adventure is fun. We’re designed to enjoy our desires and seek a partner. When in love we feel attractive and believe in possibilities. Everyone should have a Romance like that. It’s something to remember, to muse about later.

Still, the truth about romantic love and marriage is bitter. Babies are abandoned; partners are beaten; vows are forgotten. Even the most realistic of us cling to the hope that our love will not have those catastrophes. We are believers, easily persuaded and naïve. In my romantic past, I have a list of sadness and failure. The list includes divorce. How did that happen? The short answer is I held faulty ideas about Romance, about what a relationship really demands, about how to be a loving partner.

My life also includes a later good marriage, good kids and supportive friends, but I’ve made serious mistakes. I’m not a romantic now, just an ignorant girl of the Fifties who watched Donna Reed be a compliant wife on TV. Sex was never spoken of in my world, nor was there information in an article by Hedda Fay in 5enses. Gay people were closeted. Transgender wasn’t even a word. So I have some excuses for my ignorance and failures. Because I’ve been a teacher, I collect and read memoirs, and the good ones describe love and the many ways it affects a life — the neglect, the joy, the suffering and longing. Many memoirs find humor in the journey. I’m thinking of classics like Mary Karr’s Liar’s Club, Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, and Jeanette Walls’ Glass Castle. A truthful life is complicated, made of Romance and wounds. These memoirs reveal all of it.

Now, having lived through some dark stuff and suffered some shocks, I believe in telling the truth. Maybe that’s why I write — to find the truth in my heart. Experience has made me skeptical about Romance, so I can’t advise that a soulmate is waiting for you. Our culture is cruel, lonely and frightening. Living above the poverty line is tough, too. Accidents happen. Illness happens. We have a lot to navigate, and it takes luck and courage.

If you turn to the internet for a partner in love, be careful and honest. Live in hope, but verify. Internet romance has led to some great relationships and some awful failures. I saw a dating ad in an upscale magazine for an online source that advertises, in blue and silver type, “Find Love Like a CEO.” I’m not kidding. It goes on to say they will find for you “unparalleled, handcrafted love” because they have “tailored connections.” I’d like to know how they manage it. With bank statements? FBI background checks? Spying in your neighborhood?

Arranged marriages, common in some cultures, probably work just as well as “handcrafted love.” I’d like to apply for their job of matchmaker, because I fancy myself a good judge of character. I’d interview you and your friends; I’d read your transcripts; I’d examine your health records; I’d meet your family and your eligible partner. It would be fun to have such power over people, and my prices would be more reasonable than those smart guys offering you love like a CEO.

When I was at the top of my teaching career and believed myself to be a super-teacher, fate stepped in and dumped everything over like a wheelbarrow full of rocks. Students stopped reading. They stopped verbalizing and tuned me out.

We called them hippies. Wearing granny glasses and beads, they would sing. They would surf. They made new art. They displayed kindness like I’d never seen before. They would touch and hug, but they sure wouldn’t learn — at least as I’d defined learning.

%2520(5)%2520(6)%2520(5)%2520(2).jpeg)

I never thought the hippies were delinquent or crazy, though some lived on the edge of safety. I mourn those I knew who chose to defy our standards and died young. One of them died of leukemia, provoked by drug use; another disappeared into the mountains (I have his poetry book and drawings). I still wonder about the young girl who left with a popular band member and disappeared. One girl was seduced by a teacher and ran off to give birth in her remote shelter while he continued teaching his math classes. Surprisingly, I never gave a thought to the parents, who must have been frantic.

Instead, this revolution was about me. Picture me in my classroom, baffled and befuddled. Those students in granny glasses and sandals made me laugh; they stepped over the line between authority and student, addressing me as friend. Change came like a hurricane into my tidy life. Foolishness was in the air. I watched those hippies give up pressures for teen prettiness—in fact competition itself was gone. I remember a feeling of helplessness. How could I teach reading and writing without grades?

Those flower children told us to make love not war, and they seemed to have an impact on everything. I watched as strict conventions in dress were abandoned or weakened. Hair styles got more creative — original and colorful. Huge transitions came for us women, and we became able to choose different ways to lead our lives. A new consciousness about injustice entered our thinking — mine, at least — and those with energy and ideals would not be silenced.

In addition to new thinking, wild artistic endeavors and the shedding of underwear, the hippies turned our attention to inner values, to peace and the spirit. They led us to find comfort in meditation and the study of Eastern traditions like Buddhism. The hippies forced our attention to a side of our consciousness we’d neglected. Our fixation on career, money and dieting was rejected in favor of quiet spirituality.

I think the hippies brought that mystical awareness into my traditional reasonable life. I became restless and found my schedules and routines boring. Maybe it was more than their invasion, but the new spiritual renaissance touched me, and I left my teaching to go to graduate school to study religion. No one expected that of me. I wasn’t a clerical type. I’d been divorced, seldom went to church, and was a serious teacher with lesson plans and exams. Yet I drank the elixir and took off for Berkeley.

After three years I came away with a degree in Divinity and no answers to questions that many still ponder — the meaning of existence, whether the human spirit is eternal, or whether we live in a moral universe with an ethical center. My religious studies gave me a chance to inquire and ponder, and those classes were fascinating, but they didn’t bring me solutions to those questions.

I’d pronounce answers here if I had them, but I don’t. In a way, we’re waiting for a messiah, a prophet, “a teller in a time like this,” I read in a poem. We look for a master to solve all mysteries, as Beckett shows us in Waiting for Godot. Those tired men sit in an empty place, waiting for God. I don’t find the human condition a wasteland, as Beckett does. For me, we wait in a complicated place, battered by wars, inspired by beauty, driven by competition, even lost in anxiety, but not a wasteland. If I wrote a play about the search for meaning, I’d set it in a carnival.

Some say it’s the search itself that matters, that we need to listen to a summons from our hearts. The hippies listened and found their way in a transformation of social conventions; my niece turned to shamans who channel the spirits; my friend read books about parapsychology; a colleague accepted answers from the church. That search seems to be the way to keep from giving up on ourselves and the world.

I find hope at home here in a study, surrounded by photographs of my teaching days, when hippies invaded like a cleansing wind.

O Western Wind,

When wilt thou blow

That the long rain down can rain?

Christ, that my love were in my arms

And I in my bed again.

I’ve no idea where that poem came from. A friend dictated it to me, and I can’t find the source. I’ve not forgotten those words, so fervent a call for a return of lost love, and a reminder that winds mark our days.

As I write today, winds have been howling over the oceans and threatening Florida and the Carolinas with devastating fury. If we were living in the ancient world, we’d know the gods were punishing us for our sins and we’d be searching our souls for what we’d done to deserve the torrents to come. We are, however, smarter now, and we don’t give supernatural meaning to everything that happens. Thank you, Science.

Still, powerful winds have blasted our continent, and we are forced to attend to their gusts. Storms can turn over everything. They remind us we are vulnerable to killing forces, nasty gales of an angry climate. We are weak in the face of a torrent out of control, and no match for such horrific energy. I’m not one to pretend there’s nothing to worry about. Those winds bring suffering.

Wind has long stood for change, a reminder that all things evolve, even me. I must get older and lose youthful exuberance, and so must you. Dreadful storms of war can come. A peaceful town can be hit by bombs, just as an innocent garden can be swept bare by gales. Interruptions by unwelcome change can be unpleasant, even horrendous, and the wind symbolizes all that comes despite our dreams of peace.

I have a safe place here, so I’m viewing the winds outside today with no rancor. In fact, restoration can happen on a windy day — maybe our thinking is inspired, or our dreams awakened, or our decisions enlightened with clarity. A storm ‘clears the air,’ we like to say, inviting the new and beautiful. It’s time to credit a windy day with praise.

Our town stands surrounded by desert, where the wind loves to rule, so I submit and accept. I’ll walk in the gusts and let it muss my gray hair, amused by the complaints of the busy people who dash into a calm room straightening their coats and smoothing their hair. Not me. This blast is a way to enjoy a natural moment I can’t control. My opportunities to revel in a natural setting are few: I can’t hike or bicycle or swim anymore. So the wind is my ocean, my forest.

Even with miseries from storms, this morning I can let myself think about fictional storms, like the tempest in Shakespeare bringing survivors to frolic on an island, or the whirlwind that brought God’s presence into the Hebrew mind. In addition, storms are exciting settings for struggles against the elements that are riveting in books and movies, like The Perfect Storm by Sebastian Junger, about Hurricane Grace and a nor’easter. Such upheavals in nature set creative imaginations on fire.

For prophets and poets, a cyclone can bring visions, like the chariots of fire that appeared across the heavens bringing promise. I like that biblical symbolism, so powerful and loud. While our tornadoes destroy with noise and fury, these amazing chariots come with an assurance that we can overcome (a phrase I love) and survive.

A gentle wind called spirit, which mystics have known as the source of our insights and energy, is altogether different, a spirit from the natural world bringing us closer to the infinite. Some seekers pray with an intake of breath because it contains the power of the Divine they seek. Wind of that kind contains holiness.

Anne Lamott, in her new book Somehow, tells of being hurt by an undeserved insult, like being blasted by a storm. After much soul-searching, she finds within herself “the still point of the turning world,” as TS Eliot called it. After a time, she saw that “the thatched roof of me had blown off,” and, “There I was, on a small plot of land inside . . . breathing . . ..” I like to think that in a bad storm we can find a ‘still point’ within us.

Winnie the Pooh loves a blustery day, and we see in those whimsical illustrations a furry bear and a little boy holding an umbrella as the wind pulls them off their feet. A wise Gopher advises them to leave the Hundred Acre Wood because it’s a Windsday, he says. Instead, Winnie the Pooh goes about wishing everyone a “Happy Windsday!” and proceeds to live his life protected by an umbrella.

Happy Windsday!

Archy, the cockroach, spends his time in a newspaper office and uses a typewriter after hours to comment on life. He’s unable to work the desktop computer, but he’s quite adroit with typewriter keys. I’ve had to add capital letters to his message, but he has his own opinions. He can readily spot an arrogant candidate up for election. Here’s his latest, written for the news reporter to read in the morning:

— A lightning bug got in here the other night, a regular hick from the real country he was, awful proud of himself.

— You city insects may think you are some Punkins, but I don’t see any of you flashing in the dark like we do in the country, he said.

— All right, go to it, says I. Mehitabel, the cat, that green spider who lives in your locker and a friendly rat all gathered around him and urged him on. He lightened and lightened and lightened.

— You don’t see anything like this in town often, he says.

— Go to it, we told him. We nicknamed him Broadway, which pleased him.

— This is the life, he said. All I need is a harbor under me to be a Statue of Liberty.

When he wore himself out, Mehitabel, the cat, ate him.

— Archy*

Archy sees egotism and names it. He knows a prideful braggart for what he is and warns against candidates who feel superior — who consider themselves special and like to brag. Self-important lightning bugs get gobbled up, he teaches.

We find this lesson in children’s stories, in fables from ancient literature, and in sacred texts. It seems we need to hear it over and over because we forget our lessons. Usually we’re unaware that we’re showing off as we pretend we’re modest, but there can be an Archy watching behind the scenes — a wise teacher who reminds us that we’re human and need a lesson in humility, like Jiminy Cricket, who pointed out to Pinocchio that he was untruthful.

The role of teacher is sacred. They come in all sizes, as Jiminy and Archy demonstrate. They can be wizened old grandparents, sitting with pipe in the corner of the room, or a vivacious auntie like Auntie Mame, who took a tidy, obedient boy and gave him a lesson in how to have fun and understand dishonesty in wealthy neighbors. At any rate, we need someone who tells us the truth, and helps us when we need redirecting. I had a wonderful seventh-grade teacher, Miss Miller, who stopped by my desk as I was writing and turned the paper so I could manage to write easily with my left hand. Her silent lesson changed my life.

Failure is a great teacher. I failed at a first marriage. I failed at a profession I coveted. I failed as a driver, twice. Once the ego gets smacked upside the head, we learn. And there’s so much to learn in the time we have. After failure, I’m a better driver and much wiser about my talents, and even, I hope, a better partner.

Roz Chat’s memoir Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? recreates her struggles to care for aged parents, both of whom were proud of their accomplishments. Mom was a school administrator, Dad an academic scholar. In old age they became difficult and demanding. As their only child, Chat had to cope with their enormous needs. She doesn’t minimize how hard it is to deal with self-important lightning bugs. Her story and cartoons are poignant but also funny, making the book a masterpiece of literature, in my view.

Great comedy is made of self-important characters who need the wisdom of teachers to set them straight. I’ve found some glorious ones on TV over the years. Frasier Crane is a self-important psychologist who would rather speak of his own issues than listen to people with problems; Frasier had a wise teacher in his father. Archie Bunker berates his wife because she can’t see life as he does. His children try to teach him, and their efforts are funny but never successful.

We have many smart-ass lightning bugs living among us now. We’ve seen them trying for the power to rule the world. For those who attempt to be the Statue of Liberty, exposure and humiliation are ahead, as Archy knows. When powerful people believe themselves to be superior, it seems life has a message for them — a fall from grace, a wound of failure. Like the emperor who wore no clothes in the parade, it’s dangerous to believe the praise. Those who do are liable to find themselves naked in front of reality, embarrassed and foolish.

* from Archy and Mehitabel by Don Marquis, 1916

Who would have thought that Dewey, Arizona would enrich my life? To my friends in San Diego, a move from the blue Pacific, from civilization, was unthinkable. They assumed San Diego was paradise, but for me paradise didn’t matter anymore. I had to see a new landscape. I had to see Arizona.

In Dewey I found change, and I needed change. The urge to move away from the familiar landscape where I’d taught and divorced and raised children was in my thoughts every moment. I wanted to run away from all that didn’t matter much anymore — a lackluster job, a familiar routine, the furniture of everyday. I ran to stay alive.

On my last days in San Diego classrooms, my Hispanic students understood my need for change and encouraged me to leave. I imagine they knew what it was to trek away from home. They presented me with a poster that read, “Make like a banana and split!” That encouragement softened my sorrows at leaving them. I still miss Pauline and Lillian and see them in memory all these years later.

It's like a rebirth to have to make a home in a new land. As a single woman I had to find my way on new streets, locate new services, endure shocking weather. On one memorable day I set off on a snow-covered street and noticed no other cars on the road as the flakes fell around me. Wouldn’t it dry up in a minute? I barely made it home, and when I did I couldn’t manage the driveway because of snow and ice on the hazardous incline.

The good will of neighbors saved me. They never laughed at me, but they smiled a lot. They were Midwesterners relocated to the Arizona sunshine to play golf and enjoy retirement, while I was a California native who’d never been in snow. This is what I’d wanted, and I met pronghorns, enormous clouds, silence, and people who loved rodeo.

Besides San Diego I’ve lived in Claremont, in Berkeley, and San Gabriel, where I grew up. None of these California towns had snow, but they had colleges, safe streets and even a historic Mission. They had palms and eucalyptus, orange trees and pink bougainvilleas — sweet for growing up, but I needed a new landscape even though I had no idea what living in Arizona really meant. Somehow, a contrasting land offered the bracing air of expansion for me.

Before Dewey I’d moved to Berkeley, where the vibrations were of protest, competition and wild individualism. The first day I arrived I fell over the cane of a blind man, landing flat in the crosswalk. Falling seems to be my way of coping with a confusing setting. I stumble, drop down, and see the view from below — if I’m not injured and need to be carried away. Since that day, I’ve been rescued from falls by friends here in Arizona more than once, lifted and cheered by hearty strength that saves me.

Living as a stranger in a strange land is perilous, inspiring, and scary. From the incidents above you know I don’t do it well. But new landscapes have opened and revitalized my soul. After Dewey I remarried and moved to Prescott, where I found Thumb Butte, a cozy library and the courthouse plaza. The local paper was as new to me as a monsoon.

Kathleen Norris’s experience in the Dakotas, where she chose to go in retreat, is the subject of her memoir Dakota: A Spiritual Geography. She writes, “The region requires that you wrestle with it before it becomes a blessing . . ..” Thinking at first that the landscape was barren, she found there a place that became beautiful in its emptiness, offering solitude and room to grow. That’s my experience too, a place that was at first bewildering became essential.

I’m aware that being forced to move away from a familiar landscape can also be punishing. Some immigrants must choose to walk away from family and home so they can survive. Their migration can break their hearts, and their estrangement can destroy confidence and stability. Their difficult choices are made out of necessity; mine have been out of a need for restoration, and I recognize the privilege in my free choice.

I was a muttering child, a bad sport when new family plans disturbed my day. My mother would confront me with her usual maxim, “Brighten the corner where you are!” I think she knew it annoyed me. I would never use those words today, but I did have to learn to enjoy my new corner of the world — Dewey, a landscape of quiet ranch land and a farm that sold homemade coffee ice cream.

My parents taught me values that would make Benjamin Franklin proud. They paid their taxes, voted, and saved for a rainy day. They were hardworking. They sacrificed leisure to get things done. Because I follow their teachings, I’m honest, trustworthy, frugal, and tidy.

Even though I’m heir to those American values — brought to our shores by sober Puritans — I’m more appreciative of other ways of being as I creep into old age. I can appreciate Americans who are different from me. Indeed, I like to be around people who color outside the lines, who change the narrative, who shock and criticize us.

Perhaps I enjoy those people because I can’t break any rules. I’ve rarely stepped over the line, or smoked pot, or driven too fast, or failed to appear when called. Back in the past, when couples at a summer party stripped and jumped naked into a swimming pool, I stood by, unable to unzip.

That’s who I am, the character who watches; the designated driver; the prude who doesn’t get in on the fun. It’s easy to blame my restraint on my parents with their noble principles, but at this advanced age I must take ownership of who I am. I enjoy writing about myself as I get to know me — the careful one, the map-reader, the observer.

Age has taught me to seek out people different from me, those who awaken me from conformity, those who inspire me and keep me from boredom. They are the laughter in our quiet, the excitement in the flat days, the spark in the bland air. In literature they are conniving servants, funny criminals, wise wanderers, models of mischief. Like Mary Poppins, they come into our lives bringing magic.

If we’re lucky, we’ve some friends like Poppins, ready to lift our spirits. At just the right time, they come with flowers, chocolate, or dumb jokes. When I was hospitalized, Mary Poppins came with toffee and a book. Wearing her wooly cap, she walked (or descended) into the room with light and sweets. In another form, a Poppins friend came lumbering in with jokes. He made the overworked staff look up and smile.

While I’m part of the tradition of the Puritans,whose values have made us a decent, successful, prosperous country, the Poppins people represent another sort of American — the entertainer, the giver, the adventurer who jumps naked into any water that beckons. We’d still be wearing gray, burning witches and preaching for hours if it weren’t for this other, more creative, part of our culture. I’m a fan of Dave Barry, a funny writer who shakes our complacency with humor. He defines a sense of humor as “a measurement of the extent to which we realize that we are trapped in a world almost totally devoid of reason. Laughter is how we express the anxiety we feel at this knowledge.”

Critics, like Barry, make fun of us. We need their critiques. I’m thinking of the satirists, like the one who mocked our Cold War with Doctor Strangelove, and the television hosts who make fun of our politicians. Jon Stewart is a master. Their satire serves us.

Another American spirit that awakens me has come to us through our borders, back when immigration was possible for many. We’ve been blessed by them. They’ve brought us gifts of nourishment and ease in the world, their music, their energy and enormous talents. They make movies; write wonderful books, cook new foods, teach our kids and lift our heavy loads. We would be poorer without their strength and infusion of color.